print media and class conflict

Print Media and Class Conflict

by Jonas Thoresson

for #IV. the medium is the message?

Differens Magazine, winter 23/24

What is the political use-value of media? The answer depends on how the follow-up question, ‘…and for whom?’ is answered. During the epoch of what historian Benedict Anderson calls ‘print capitalism’, from the early modern adoption of print for public use to the advent of radio and TV, such questions were often high on the agenda, whether explicitly or implicitly.[1] This was especially the case towards the end of the epoch of print dominance, in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries when ‘the social question’ – questions concerning the conflicts and grievances thrown up by the industrial revolution and often centred on class – was both hotly debated and fought out in revolutionary struggles. In the midst of this uproar of modernity, print media appeared in a dual guise, simultaneously promising enlightenment and threatening subjection. Focussing on the British context, these are the themes and questions I puzzle around in what follows.

Marshall McLuhan largely evades such questions in his influential media theories. In Understanding Media (1964) he is primarily interested in understanding how media affects our sense of time and space, and argues a radical technological determinism by suggesting that ‘the formative power in the media are the media themselves’ with little attention to their actual uses.[2] To be sure, there are things to be gained from a focus on mediality, or the affordances of specific media, but the problem with McLuhan’s media theory is that he wants to radically detach mediality from both its socio-economic conditions of production and the cultural uses of media. A cogent example combining the focus on mediality with attentiveness to conditions of production and the cultural uses that audiences make of media can be found in Imagined Communities (1983), where Anderson draws on print media to explain the emergence of modern nationalism. He argues that modern newspaper readers, all reading their daily newspaper as a substitute for morning prayers, as Hegel famously put it, thereby constructed an imaginary solidarity among strangers. The simultaneity of reading habits facilitated by the daily appearing newspaper, in Anderson’s take, encouraged a shift in temporal conception from what Walter Benjamin called ‘Messianic time’, in which the present is imbued with both the past and the future, to ‘empty homogenous time’, or clock-time, a conception of time also necessary for labour to become a real abstraction.[3] Anderson’s account carries an explanatory force which is often lost in McLuhan’s musings, however suggestive they may be.

Habermas offers a study similar to Anderson’s in its sensitivity to the interplay of mediality, production, and cultural practices in The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere (1962), where he considers how the novel and the discursive essay journal as print genres each contributed to the formation of the private and public spheres, respectively. But where Anderson is interested in the emergence of nationalism, Habermas is concerned with elucidating the conditions for rational-critical debate capable of influencing society. He finds in the classical bourgeois public sphere (Öffentlichkeit) a cultural space, between the private sphere and the state, for critical-rational debate on matters of common concern and in principle open to all. While early romance novels helped constitute a private, intimate sphere, journals like the Tatler and Spectator played a key role in the formation of a specific type of polite sociality. The discursive style of these journals materialises the dialectical relationship between print media and the lifeworld of the coffeehouses and literary salons of Enlightenment Europe: articles were both written and read in these cultural settings, and the reader found in the discursive style of the journals a model for emulation in speech. Through such journals, a public opinion could take shape and influence the state. Habermas’s model has been subject to much valid critique, often targeting his overly idealised picture of the bourgeois public sphere. Some of these concerns can be offset by turning to alternative public sphere formations like the proletarian one, which was made up of far more humble and culturally diverse participants. But more importantly, the prospect of allowing communication rather than money or power to steer society in common is even more tantalising to those without political power or capital. Indeed, the normative kernel of the public sphere, the promise of influencing society by means of rational deliberation free from coercion, belongs as much to the bourgeois public as to those it sought to elide, suppress, and exclude. There is a powerful snapshot of an oppositional, proletarian, public sphere that erupted in Glasgow in the early decades of the twentieth century. In 1919 after what became known as the Battle of George Square in Glasgow, when striking workers demanded a forty-hour working week and were met by a police baton-charge and the deployment of troops and tanks to the city, Charles Masterman (Liberal M.P. and erstwhile head of the Wartime Propaganda Bureau) left the following description of the cultural space which had fostered the strike movement in the years leading up to 1919:

They are talking continually, day and night, in a seven-day week, in meetings held outside the works gates, before breakfast, in the dinner-hour, or in surrounding halls in the evening. They are preaching, and with enormous energy, something in the nature of a crusade. […] It is scarcely “Bolshevism” […] But it is a creed denouncing “capitalism” and all “idle wealth”; a belief – whose sincerity need not be doubted – that by the reduction or elimination of the profits and interests of capital, and a direct attack on the great landlord and millionaire, the working people may found a new society, and get rid of their present disabilities. It is at present a “revolutionary demand,” and Glasgow is the storm centre of Britain. One can judge by their bulletins, their vigorous combined action, their replacement of leaders when arrested by other leaders, how completely this creed has mastered the upper guiding group of the strikes organisation.[4]

The dynamics and problems of such a public sphere, steered by an emancipatory interest, were quite different from its bourgeois rivals. The proletarian public sphere was caught in what Richard Johnson calls the dilemma of working-class printers and educators: on the one hand, they aspired to pursue a project of enlightening debate with practical ends together with its working-class audiences, that is, to represent and coordinate resistance to the liberal project of modernisation so lavishly promoted in the mainstream press, and later to seek means of control over the infrastructure that this project had yielded.[5] On the other hand, they pursued that project under limiting conditions – limited time and resources or purchasing power among its readership, and limited energy for autodidactic activity. But by the turn of the twentieth century, however, the structure of the public sphere had changed considerably in ways that presented new challenges to working-class publics seeking to improve their common lot.

The nineteenth century structural transformation: commercialisation and taste

The repeal of the ‘taxes on knowledge’ (chiefly stamp, paper, and advertisement duty) in the latter half of the 19th century marks a decisive shift in the material conditions of the public sphere. It marked the beginnings of a newspaper industry increasingly under the sway of commercialisation. In the early nineteenth century, radical publications were outcompeting their bourgeois rivals in circulation numbers. They did so under conditions of relative technological equality, and E.P. Thompson describes the radical plebeian weeklies of 1816-1820 as means of propaganda in their fullest ‘egalitarian phase’: ‘Steam-printing had scarcely made headway (commencing with The Times in 1814), and the plebeian Radical group had as easy access to the hand-press as Church or King.’[6] To quell the influence of the Radical press at a time of momentous social and economic transformation, the British state turned to sanctions in the form of taxes and outright suppression. While the Radical publications were thus driven underground, liberal campaigners sought to remove the barriers to commercial competition and thereby place the provision of newsprint in the safe hands of wealthy newspaper proprietors. The advent of steam printing meant that any newspaper enterprise was in need of significant capital outlay to stay competitive, thus limiting the possible owners to those who had either access to sufficient capital on their own, could secure loans, or attract enough advertisers. It was particularly the need to attract advertisers that had troublesome and unforeseen consequences, not just for socialist printers, but for the old respectable press too. The advent of commercial newspapers, printed by steam and beholden to advertising revenues, led to a crisis of taste among editors and journalist of the respectable press, who found themselves forced to adjust their style, to write up or down, to readers approached as consumers.

To editors of old respectable newspapers like the Glasgow Herald, founded in 1783, the structural shift was met with a mixture of fear and excitement. The Glasgow Herald had acted as a regional platform and informer for the local merchant and industrialist classes since its earliest days, and staunchly promoted the liberal-imperialist project of improvement based on free trade. When the first daily issue appeared in 1859 it was set to enter the local daily market as a competitor to the North British Daily Mail, which had dramatically overtaken the Glasgow Herald’s circulation after the repeal of stamp duty in 1855. The move had necessitated new investment in coal-powered printing presses and the excitement of the proprietors is signalled by the inclusion of a poem at the top of the prestigious literary section of the newspaper:

Old King Coal was merry old soul,

A merry old soul is he;

May he never fail in the land we love,

Who has made us great and free.

While his miners mine, and his engines work,

Through all our happy land,

We shall flourish fair in the morning light,

And our name and our fame, and our might and our right,

In the front of the world shall stand.[7]

But by entering the daily market for print, the Glasgow Herald simultaneously found itself confronted by what its journalists and editors found to be terrifyingly low tastes, not just on the part of its commercial competitors, but also within a new segment of the reading public. The leading article of the same issue put it this way:

It is a miserable mission to pander to a depraved taste; and we are ashamed to notice that some periodicals, usurping the title of newspaper, have made a trade of serving up trash in the style of the mysteries of London or Paris, for the special use of those who have not information or strength of mind enough to resist the pestiferous influences which such writings communicate.[8]

This anxiety over taste shows an editorial staff in the grip of forces beyond their control. The pressure to attract advertisers meant that editorial writers were forced to write up or down [jt11] to readers, now approached as consumers. This threatened to disrupt an old community of readers organised around a shared taste, which meant that they had to either transform or differentiate. The Glasgow Herald chose the latter solution and split its readership with the lighter and more jocose evening paper the Glasgow Evening Times, centred on sport, police reports, and ‘entertainment’, but little political content – a true representative of the new commercial press. A style borrowed from the radical plebeian press, but given a new layout and content adapted from the bourgeois press thus emerged with two important ideological consequences.

First, the project of taste had its own ideological problems. In the high-end newspapers this project of protecting good taste can be seen in the careful containment of an aesthetic sphere through layout, for example by specially designated literary pages, designed to preserve a space for art and literature in allocated columns. This way of containing aesthetics signals a conception of culture elevated to abstraction signalled by the capitalised ‘Culture’, inherited from the Victorian post-enlightenment cultural critics. I think here of Thomas Carlyle, who was held dear to the editors of the Glasgow Herald. In Carlyle’s hands, culture was construed as a project of private moral compensation for the ‘mechanical’ world of industrial capitalism and imperial bureaucracy.[9] Somewhat paradoxically, this model of privatised cultivation undertaken by the solitary reader points towards the emergence of a consumer subjectivity.[10] While designed to protect a sense of moral dignity for the individual adrift in the new industrial society, the ideological effect of this firm allocation of moral cultivation to the private sphere is plain: it strips the public sphere of moral evaluation, in favour of instrumental reasoning according to predetermined ends. By linking aesthetic evaluation to moral judgement and privatising this sphere, both intellectually and in the material layout of newspapers, a new subjectivity, split asunder, was encouraged. Max Weber sought to capture this split in modern subjectivity when he spoke of utilitarian ‘specialists without spirit’ and hedonistic ‘sensualists without heart’ in his early twentieth century diagnosis of the times.[11]

And second, the newspaper medium with its abstract allocation of categorically separated ‘content’ alongside display advertisements determined by the cost of the advertising space, helped constitute a new subjectivity or role, oriented to reception in the private comfort of the home. This shift mirrors the constitution of a newly circumscribed political subjectivity: the citizen as member of an aggregated electorate (emerging gradually with the expansion of the franchise in the late 19th century) exercising political freedom, not so much discursively, as by signalling approval at the ballot box. The commercial newspaper played a role in fashioning this narrow form of representation: by monitored readership figures (measured in circulation, or sales) a more mediated form of representation could be mobilised in public discourse, so that the figures of a readership could be contrasted favourably with the number of participants in a street protest, and thereby delegitimise the older embodied expression of discontent.

This was the structurally transformed print public sphere confronted by proletarian socialist printers, who could no longer compete on relatively equal terms with the commercial press, as the plebeian Radicals had done. The commercial appropriation of a popular style, used to clothe a depoliticised content for commercial gain, made that very style suspect to socialists. Thus, a writer for the monthly periodical The Socialist lambasted the sensationalist elements of even the few avowedly labour-supporting papers:

Why should a journal, seriously seeking to advance the working class, encumber its pages with sensational police court news and all the filth of the divorce courts? […] it is foolishness to think that such matter can assist the working class in its efforts of emancipation.[12]

But the strategy for counteraction differed widely from the project centred on taste. For socialist printers the transformed print public sphere meant that the critical and educational role of their weekly or monthly publications assumed new significance.

The educational imperative of socialist print

The educational imperative of this proletarian formation echoes that of the earlier plebeian formation. As charted by Richard Johnson, the radical plebeians mobilised their journals for a radical enlightenment project of what he terms ‘really useful knowledge’ – an educational project consciously contrasted with the notion of merely ‘useful knowledge’ advanced by utilitarians like Henry Brougham, founder of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (SDUK). Against the diffusion of practical knowledge for industrial application and education in constitutional principles advanced by the lavishly funded SDUK and aimed at working-class readers, the radical press retorted with ‘What is useful ignorance? – ignorance useful to constitutional tyrants’ and ‘What we want to be informed about is – how to get out of our present troubles.’[13] A century later, the mainstream labour movement had come to endorse an educational programme directed by the state and focussed its efforts on campaigning for increased provision, but on adult education very similar concerns were raised about the subjugating and misdirecting effects of liberal education. In a clash mediated by the Forward, one of the central Scottish print platforms for intra-movement debate in the early 1920s, representatives of the Marxist Scottish Labour Colleges attacked the liberal curriculum of the Workers’ Educational Association in the following way:

Education for what? – What does the organised worker want education for first and foremost. To enable him to “talk” Geology? to appreciate Art? to discourse learnedly on Church Music? The organised worker needs an education that will help him to solve his industrial and political difficulties.[14]

The counterposing of aesthetic education to really useful knowledge made by this proponent of the Scottish Labour College offers a segue for understanding the cultural conflict between proletarian and commercial media. The highly purposive model of education, materialised in the layout of proletarian periodicals, as we shall see, formed part of a wider praxis-orientation.

The practical, organisational role of periodical print in working-class politics of the proletarian phase can be seen in how the weekly or monthly periodical was turned daily in moments of intense political conflict. The special bulletins, which Masterman took note of in the quote above, would be printed for purposes of mediating collective struggle, and a Strike Bulletin was printed on the Socialist Labour Press in Glasgow in January 1919, as a tool for the Forty Hours Movement. A similar bulletin, The Worker, was used in 1915-16 during a confrontation between workers, organised through the Clyde Workers’ Committee, and local employers and the Ministry of Munitions over the implementation of industrial organisational structures geared to optimise production of munitions during the war. Periodicals like The Worker and the Strike Bulletin facilitated communication between workers in different industries during these struggles, but they also mediated struggles elsewhere in the world, from India to the South Africa, to Canada, and thereby created an internationalist imaginary of solidarity to rival and disturb, if only briefly and in a moment of crisis, the imagined national communities. The sporadic, intermittent publication of such journals at moments of crisis also disturb the stability of empty homogenous time, by presenting a rival notion of messianic time, in Walter Benjamin’s sense.

From the perspective of proletarian publishers, however, the aim of newspapers was to construct continuity for political praxis. Thus, contemporary socialist and communist leaders emphasised the organisational value of newspapers, as tools of action co-ordination. In this vein, Lenin put forward a working-class newspaper model for Russia in What is to be Done? (1902), which presented the project of a regularly appearing newspaper as at once practical and educational, and Gramsci focussed much of his attention in the Prison Notebooks on analysing the role and organisational value of newspapers, which he described as political parties in their own right. This view of the newspaper can be better understood when considering the various forms of labour going into the production and distribution of a radical print newspaper, which often relied on infrastructure different from the commercial systems of production and distribution: their presses where old-fashioned (still, at times, hand-cranked) and operated by volunteering printers and compositors, the newsagents might refuse to stock or display the paper, and so alternative systems of distribution via political meetings, union or party rooms, or via shared subscriptions. Even in Britain, where literacy rates were very high by the 1880s, working-class reading practices also differed, and oral reading both publicly and privately was still common: in the Marxist study circles in Glasgow, it was common practice when studying Capital for the students to take turns reading the text out loud. In such a context, the special value of print as a practical and organisational tool receives a distinctive valence in addition to its more symbolic function of constructing imagined communities, as proposed by Benedict Anderson.

Underpinning the central theoretical role of the proletarian newspaper in the framework of revolutionary leaders like Gramsci and Lenin was a slogan committed to print in 1883 by the Social Democratic Federation: Educate, Agitate, Organise. The projected temporality of such activity was less explosive, and more geared to the everyday temporalities necessary for learning, whether the goal was to achieve social revolution in one fell stroke or more gradual reform. A closer look at the Glasgow-based journal The Socialist will shed light on the educational role of proletarian print media.

The organisational logic of proletarian periodicals

Generally, proletarian periodicals do not display such a clear separation in formal layout between moral matters construed as private from public matters to be approached in a calculating, instrumental way. The prevalence of poetry in these periodicals, and their insertion side-by-side with serious and topical leading articles, reinforces the sense that what was to be construed as a matter of public concern was to be directed also by moral imperatives. But this is not to say that these periodicals lacked an organisational logic. The proletarian press was purposely organised as educational media. The same press used to print The Worker and the Strike Bulletin was also used to print the monthly journal The Socialist, the party organ of the Socialist Labour Party, and akin to other monthlies such as Justice (Social Democratic Federation) and The Call (British Socialist Party). Viewed as a medium, The Socialist materialises the political programme captured in the slogan ‘Educate, Agitate, Organise’, by projecting an ideal educational progression anticipated for the readers, and designed to guide them on the path of understanding. This can be illustrated by considering its typical formal layout.

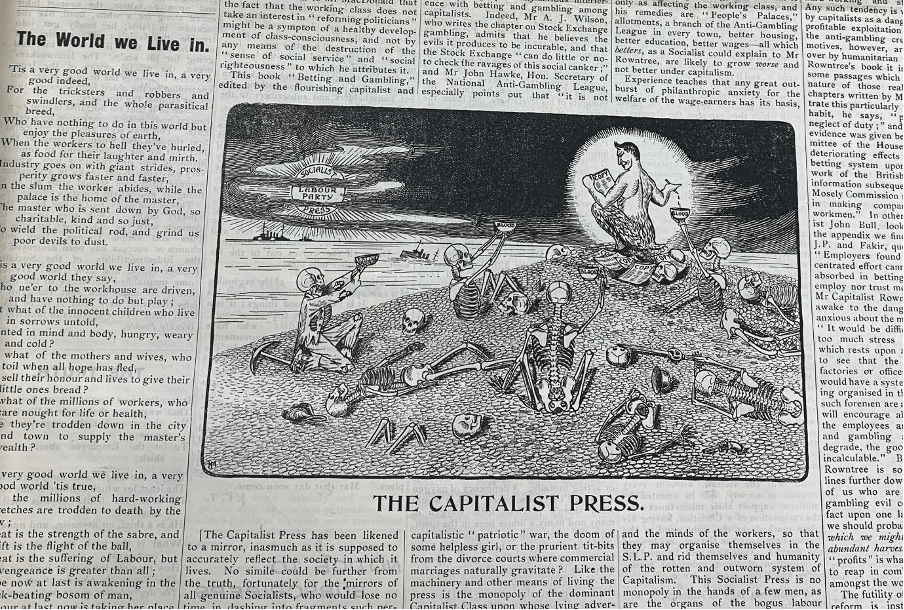

The front page would usually hold a large illustration depicting bold types intended for effective communication – emaciated workers tangled up in machinery directed by fat capitalists, angelic personifications of Socialism wielding the sword of justice against Capitalism’s dragon, demonic figures filling the pages of commercial newspapers with ink of blood against a backdrop of black-clouded skies, breaking up over the horizon by the rays of the Socialist Press, etc. Printed in broadsheet format, these illustrations covering three full columns or more under the masthead would be large enough to be used as posters, to be pinned on a factory wall or in some public space, or to be held aloft by a public orator using the illustration to elucidate a key point. The front page thus projects the initial reception setting: the meal-hour talk at work or the soapbox oration on the street corner. The second and third pages assemble the leading article with shorter pieces combining news and opinion – often with reference to the shortcomings of commercial newspaper’s reporting – dealing with topical subjects such as ongoing strikes, protests, or campaigns. These are often written in a polemical style which somewhat levels the distinction between the spoken and the written. Arguments thus materialised in print form are held in suspense, enabling closer study in settings removed from the high energy of street-meetings and witty style of public oratory. Further into the issue, longer, full-page articles appear. In The Socialist these areoften either detailed reports on important conferences of the trade union movement or the Second International (until the formation of the Third International) and reprints from an emerging Marxist canon, all intended for close study. The last pages and the backmatter contain reports from branch meetings, demonstrations, and upcoming activities: advertisements for study-circles in different localities, as well as lists of literature divided into categories of ‘beginner’ and ‘advanced’ with short descriptions. Lists of technical keywords with short explanations are included either next to the literature lists or to the longer reprint articles, as a study aid particularly to Marx’s writings. Another frequent genre is the how-to guide, where the reader is offered advice on how to organise and conduct street meetings, meal-hour talks at the workplace, and formal study circles. A somewhat humorous example of this is found in an early issue of The Socialist, where the writer provides detailed guidance on how to organise and conduct a soapboxing street meeting, an account which provides a snapshot of this dynamic public culture from before the great geographical transformation of metropolitan cities designed for car-traffic:

In answering questions [from the audience] the speaker should always be courteous. He may be asked some stupid or silly questions, but let him bear in mind that our class has had small chances to educate themselves on their own class interests. But should any “fakir, freak, or fool” dare to cast ridicule on our Party or principles, then the speaker should wade into and annihilate him, as a street crowd always like to see a smart (?) chap get a take down.[15]

This article also shows an attitude to the cultivation of sociality quite different from the bourgeois emphasis on taste. While a form of politeness is certainly not discarded, little effort is made to refine speech for elegance. Quite the opposite: the speaker is encouraged to deliver the speech in ‘straight plain English, so that all may understand.’ This way of pitching the new worldview of class struggle in a register familiar to the audience is designed with the intent of flattening the barriers of entry to the public sphere, rather than erecting stylistic barriers by means of cultural distinction.

In this way, the periodical is designed as a guiding tool that navigates the audience, as either listeners or readers, from the distinctive cultural settings first of public oratory, then of the private study and the organised study circle, and then back again to the street/factory floor setting, equipped with new knowledge and practical agitational skills. The periodical thus materialises the slogan ‘Educate, Agitate, Organise’ in both formal layout and use.

But furthermore, the pedagogical quality of the periodical signals an expectation of effort from the reader, quite distinct from the easy flow promoted by the style of newspaper articles intended for leisurely consumption. Another aspect that signifies the anti-commercial tendency of the periodicals is their durability, both materially, printed on thick paper with pagination stretching across issues (signalling an expectation to have them bound in volumes), and temporally, by issuing reprints to be read and read again. That The Socialist was printed primarily for its use-value, rather than its exchange-value, is also shown by frequently appearing prompts printed with bold type: ‘Pass this paper on to a mate’[16] ‘When you have finished with this paper pass it on to a friend.’[17] Such prompts signal an attempt to maintain a subjectivity expressed through what Raymond Williams terms residual and oppositional notions like ‘absolute brotherhood, service to others without reward’, while appropriating them within the framework of modern socialist ideology.[18] The proletarian periodical was a key medium for maintaining and reconstituting such a culture.

I described the pedagogical layout of the periodical as ‘typical’, but there is a caveat here, because the pressures of money and administrative power deeply affected both the regularity and formal layout of these periodicals. Kevin Gilmartin even speaks of ‘a form deformed’ in relation to the periodicals of the plebian phase, which often display irregularities in volume and issue sequence.[19] And alongside the longer-running examples I have cited, newspaper archives record many failed attempts in the face of such pressures. Thus, the Proletarian Schools (an educational initiative directed towards children and young people on the model of Sunday schools) issued three different periodicals in the space of only a few years (The Red Dawn, The Revolution, and Proletcult), while The Vanguard, the paper of the socialist schoolteacher and first official Bolshevik Consul to Britain, John Maclean, was suppressed after only a few issues. Meanwhile, maverick writer-editor-printer-publishers like the anarcho-communist soapbox orator Guy Aldred would consistently issue new periodicals and pamphlets printed using an old letterpress. These examples, all from Glasgow alone, illustrate the real dilemma in which proletarian media were enmeshed, between aspirations for critical knowledge with practical intent and severe limitations of resources, time, and energy.

Some Conditions for Critical Rationality

This cursory glance at the dynamics of proletarian print media, whose use-value was understood to lie in the critical education they offered to a collective project of emancipation under difficult conditions, offers an opportunity to reflect on the contemporary conditions for the public use of critical reason. The already posited dilemma of the radical educator points up the key issues: time, resources, and energy are necessary to meet aspirations for critical knowledge (and by extension, to practically organise for emancipation). To specify the list of resources needed, I would add that alongside the right kind of reading matter, the right kind of cultural spaces are needed. Masterman’s description cited at the beginning of this piece draws attention to some of the localities housing the proletarian public sphere. Some of these were more makeshift than others. Thus, the factory floor could be used, at least when the foreman was out of earshot, but more stable were the numerous halls in the city: these included the trades’ halls, meeting rooms of political parties, and the newsrooms of co-operative societies. Without such relatively autonomous public spaces, the possibility of deliberation is significantly hampered. Furthermore, with regards to time as a condition for critical rationality I would add that a specific kind of time is necessary. This is not to downplay the need for an abstractly conceived quantity of time; Masterman’s description again shows how the talking constitutive of the proletarian public sphere was carried out not just in distinctive cultural spaces, but also in the temporal margins left over after capital had staked its claim, in the morning, the meal-hour, the evenings, and on Sunday afternoons. But in addition to this, a temporality conducive to attention is required. The busy flitting of the gaze across the page of the commercial newspaper interspersed with advertisement and types of content seemingly without organic relation to one another poses a real challenge to the formation of a holistic worldview necessary to map the main social tendencies, and to discern possibilities for action. But at the same time, too much of the solitary reading in the quiet comfort of the home might also be detrimental to emancipatory praxis. This was why The Socialist sought to direct its reader-hearers from the busy street-corner to the focussed study circle, and then back again. This shifting between spaces and temporalities conducive to both critical learning (grounded in sustained attention) and collective action is a demanding prospect today. Contemporary advertisement-driven digital platforms present even more challenging foes today, by virtue of their form and operational logic, than the commercial newspapers of the early 20th century could dream of. Alongside campaigns to reclaim public spaces, campaigns to reshape digital (and print) media such as those proposed by the Media Reform Coalition offer some potential avenues for reform. Meanwhile, other tactics are worth considering, and I will close out with a productive approach to aesthetic objects which I think is a good supplement to programmes of political reform.

Aesthetic education was often viewed with suspicion within the proletarian public sphere. But this had more to do with its inflection as the development of taste – a project which can easily slide into the development of refined consumption habits, as the connection between taste and the metabolic system already suggests – than with a general hostility to aesthetic expression and evaluation. Indeed, there are alternative ways of appropriating art to the ones discussed above. For example,] Habermas pointed to the possibility for enlightenment in communication using aesthetic objects as points of reference in an intervention into the postmodernism debates. He did so by citing Swedish-German author Peter Weiss’s novels, where politically motivated workers in late 1930s Germany meet up in the public museums of Berlin to discuss art, to appropriate it to their own needs and self-understanding, and as a means of critique under conditions of severe political repression (a form of repression which meant that other ways of organising were largely off the table anyways). Their method for doing so bears close resemblance to the model projected within Enlightenment notions of Bildung, whereby the audience of an aesthetic work seeks to mediate between specialist aesthetics and everyday life. The formative and world-disclosing effect of this aesthetic encounter – of seeing the world otherwise, including as it is not but promises to be – can shape both politically relevant motivations and understanding, or class consciousness. When pursued by subalterns seeking collective ways out of pressing difficulties, this method can take on a more emancipatory direction than the emulation of gentlemanly sociality undertaken by the aspirational individual, the construal of an intimate sphere of pure humanity, or the related protective moral project of the romantic cultural critic.

Footnotes:

[1] Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities (1983)

[2] Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media (1964) p. 21.

[3] Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities (1983) p. 24.

[4] C.F.G. Masterman, ‘Labour Unrest’, Daily News, 11 February 1919, p. 4.

[5] Richard Johnson, ‘“Really Useful Knowledge”: radical education and working-class culture’ in Working-Class Culture: Studies in History and Theory (1979).

[6] E.P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class (1962) p. 739.

[7] Glasgow Herald, 3 January 1859, p. 3.

[8] Glasgow Herald, 3 January 1859, p. 4.

[9] See Carlyle’s essay ‘Signs of the Times’ (originally published in the Edinburgh Review in 1829).

[10] For a close reading, see Alex Benchimol, Intellectual Politics and Cultural Conflict in the Romantic Period: Scottish Whigs, English Radicals and the Making of the British Public Sphere (2010), pp. 130-148.

[11] Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic (1992) p. 124.

[12] ‘A Working Class Paper’, The Socialist, February 1911, p. 44.

[13] See Richard Johnson, ‘“Really Useful Knowledge”: radical education and working-class culture’ in Working-Class Culture: Studies in History and Theory (1979).

[14] ‘Workers’ Education’, Forward, 29 July 1922, p. 8.

[15] ‘Regarding Outdoor Propaganda’, The Socialist, October 1904. The term ‘fakir’ referred to official leaders in the labour movement – Daniel De Leon, a strong influence on this particular Scottish Marxist formation, uses the term labour ‘fakers’ in his pamphlets to refer to the same type of official, and the term may have morphed in the British context to receive an orientalist inflection.

[16] The Socialist, 18 September 1919, p. 3.

[17] The Socialist, December 1915, p. 19.

[18] Williams, Marxism and Literature (1977) p. 122.

[19] Kevin Gilmartin, Print Politics (1996) p. 88.