the atmosphere of climate change

The Atmosphere of Climate Change

by Nicole Miller

The Atmosphere of Climate Change is a multi-faceted research project undertaken in 2019-2020 that involved interviews, imaginings, media studies, artificial intelligence and the creation of experimental artistic films to explore the atmosphere constructed around the topic of climate change.

for #IV. the medium is the message?

Differens Magazine, winter 23/24

Neural Networks and the Study of Atmosphere in Media Images

Me: Is there a media image you recall that reminds you of climate change?

Participant: I don’t have one media image – just a big cloud of stuff that isn’t easily separated.

During an interview with a participant about their memory of climate change images, I was intrigued by the statement that a “big cloud of stuff” was how the topic was mentally revisited. This response alludes to the atmospheric content I wanted to extract from media images, assuming that viewing many images creates an overall atmosphere – a feeling – around the topic of climate change. In order to study the inseparable cloud of atmosphere around images, I implemented the use of a neural network. Atmosphere is a concept that can be difficult to pinpoint due to its invisibility and indescribable qualities, which are sometimes linked to emotions. Therefore, it can be difficult to investigate it. I chose to study the atmosphere through a combination of a defined set of aesthetic properties, such as: color, contrast, shape, and composition. In this way, elements contributing to the construction of an atmosphere can be identified in a quantifiable manner. These properties are similar to those used in art history for interpreting artworks.

Together with individual interviews about imagination, I gathered a collection of 2,000 photographs found on Google Search using terms like “climate change”. There are limitations for a human to analyze a data set this large for commonalities. In addition to the quantitative limitations of human analysis, the complex man-made elements found in the images become an obstacle for discerning the subtle and more aesthetically-based atmospheric qualities of the images. For instance, many of the images contain the earth, but interpreting the images based on color and shape becomes more complicated when human cognitive programming recognizes both the symbolic meaning and signified object in the images. Objective analysis is diverted by human filters which condition humans to be visually literate.

To address this problem, I collaborated with a Research Assistant at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen who worked with machine learning applications in architecture. I collaborated with him to use machine learning as a tool for my analysis. My goal was to have neural networks “think through atmosphere.” In early discussions about the technical details, it became clear that what I wanted to do would not result in clear images of climate change. The method I was interested in is typically used for generating pictures of objects like human faces or animals. Since humans and animals have a particular external form, neural networks can be trained to recognize and replicate them based on common visual similarities in the input data. With climate change, the result would not be the same since the concept is visually elusive and diverse in its representations. In consideration of this, I decided it would be interesting to use neural networks to study an extensive library of climate change media images and then generate images reflective of the collective atmosphere of all of the images.

Artificial Intelligence and the training of neural networks is based on imitating the processes of how the human brain solves problems. The novelty of my machine learning-application is that it is used to reduce human filters, and to allow a formal analysis of the aesthetic patterns present in the collection of images. In particular, during the project’s execution in 2019 and 2020, using neural networks in humanities research was a new approach.

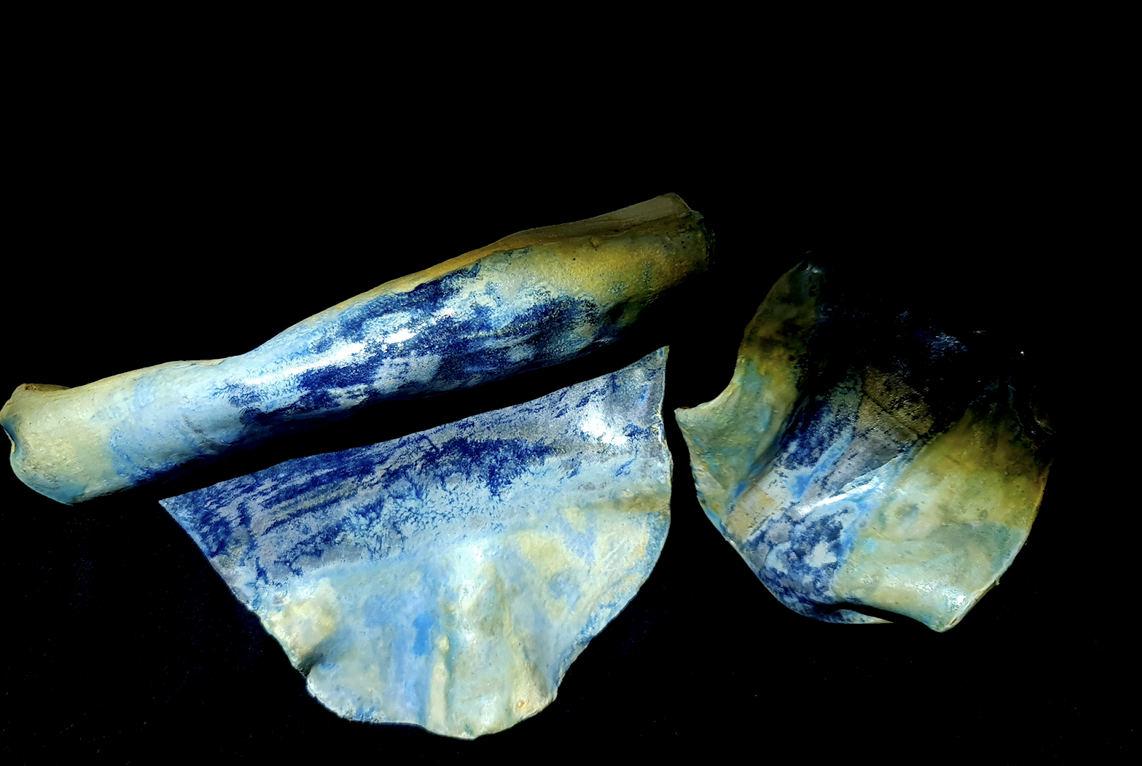

The technical procedure functions similarly to a human’s intake of images. We implemented a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) framework (Goodfellow, et. al 2014). Training began using 2,000 climate change images as the input data. The training consisted of two networks working together where one, “the discriminative network”, functions as a teacher, and the other “the generative network”, functions as a student (ibid.). The student attempts to create a “climate change photo” beginning with noise, and the teacher judges if it is real or fake based on similarities with the input set, giving feedback to the student on why it is not correct. The student gets better and better at accurately generating something that can pass as a “climate change photo” through repeated attempts and feedback from the teacher. Ultimately, this processual learning results in images that illustrate patterns of aesthetic elements such as color, shape, contrast, and composition, that are deemed by the networks to correlate to climate change photos. I like to think of this as the student imagining climate change. As training progresses, each generation of images gains precision and appears as a smoother, more decisively made image with a higher correlation to the input set. The outcome of the process is similar to human intake of media images, where in the end a single image of climate change may not be memorable. Instead a blur of aesthetic qualities and intuitive feelings of the images one has seen may be more prominent. The neural networks create more precise images in the same way a thought slowly becomes more explicit in a human’s mind or the flow of a film becomes more complex after starting from black.

The training resulted in 16,000 images, depicting the atmospheric qualities of climate change through recognition of the repetitive aesthetic elements in the input set; the generated images serve as a medium for visualizing the atmosphere of climate change. The resulting atmosphere is, interestingly enough, similar to how the interviewees described their imagined climate change objects. This goes to show that there is an apparent connection between the human imagination of a mostly invisible concept like climate change, and the intake of media images. The application of a GAN-framework is novel in that it gives insight into the process of creating an ‘atmosphere’. It makes visible how media contributes to a cultural construction of the atmosphere of climate change, that lives in the imagination of media consumers.

Atmospheric Construction in AI Images

Finding common indices and specific aesthetic properties used to convey ‘climate change’ provides a means to analyze atmospheric construction. This is significant because in the construction of atmospheres lies the ability to influence and exercise power. Deconstructing semiotic commonalities reveals the processes at work, which in turn detracts from the potential influence of images.

The input images used to train the neural networks reflect common indices and symbols of climate change. Charles Sanders Peirce (1991) differentiates between an icon, an index and a symbol; icons resemble what they are depicting, whereas an index gives an indication of what is depicted (e.g. smoke is an index of fire), and a symbol has no relation between the visual depiction and the meaning. The input images of climate change are iconic in that they are photographs which resemble their real-life subjects. A photo of a fire resembles the fire in reality. However, climate change images are iconic in their depiction of specific indices, but not in depicting climate change itself, because climate change cannot be captured in a single photograph. This is why indices are vital to examine; they are the means by which we are able to see climate change through their implication of its existence. One might also argue that many (or even all) depictions of climate change are symbolic. Humans interpret the many images and indices as symbols of the idea of climate change, as they are often removed from a direct connection to their content. An image of Greta Thunberg, for example, is symbolic rather than indexical of climate change. Whereas images of glaciers melting can be considered indexical of the existence of climate change. I would argue that the more a symbolic image is used, the more it can be mistaken for an indexical image. In the example of melting glaciers, every photograph of melting ice taken since the beginning of photography is not necessarily an index of climate change. I find it important to emphasize this, as the symbolic cultural significance of an image can often convolute the precise content depicted.

There are some standard indices in images of climate change that are used to visually signify its existence. Many indices and symbols are repeated in conventional climate change images over and over again creating a visual language. The first is the use of the Earth or the sun changing form. The Earth is often depicted as flaming or melting. The spherical shape is pervasive in many images, even in subtle composition. This was reflected in my interviews as approximately 40% of participants who were asked to give a shape to climate change imagined climate change as a circle, sphere, or ball, often referencing the relationship to the Earth or the sun when asked to reflect on this choice.

Secondly, fire is a standard index of climate change. Many images illustrate the Earth on fire or simply depict large scale fires accompanied by smoke. Many participants cited images of the Amazon burning as influential, which can be explained by the fact that many of the interviews were conducted in 2019, coinciding with large wildfires in the Amazon. As a result, smoke and fire were often found both in the collected Google search images and referenced by participants.

A third common index of climate change is melting ice. The input images I collected show glaciers, glacial retreat, and floodings. Many images are of landscapes in the process of changing through extreme events. Indices like these are typical of visualizing climate change, and the patterns were also represented in interview responses from participants. As such, we can detect their relevance in creating an overall atmosphere around climate change, where their repetition and underlying tone seems to affect imaginings of climate change.

The AI images I’ve generated are reflective of a transition to Delueze and Guattari’s (1987, 570) smooth space. Delueze and Guattari differentiate two different types of spaces: striated space and smooth space. In striated space, a clear orientation and a central perspective is constructed by elements of human engagement. In smooth space, on the other hand, its “orientations, landmarks, and linkages are in continuous variation” (Deleuze, & Guattari 2013, 573). Conceptually these can be understood as: the concrete and precise derived from the ability of striations to characterize and clarify versus the abstract and imprecise atmosphere of a space characterized by a transitional fluidity. The space of the neural network generated images is less oriented, less clear, and more abstract in its ability to be traditionally interpreted; the training of neural networks demonstrates a means by which to remove the central perspective and human orientation of a 2D image to move from the striated space of a traditional image into a fluid smooth space. In media studies, these new type of images are of potential interest for analyses. Through this process, newly generated climate change images are removed from indices of climate change and instead intuitive elements become more visible. The process used helps to directly visualize the atmosphere of climate change by focusing on invisible abstract qualities and de-emphasizing specific indices and specific objects and environments. In the smooth space of the new images, an underlying atmosphere shaped by the media can be seen. The resulting output can be considered as a deconstructed visual language of climate change communication.

The generated images demonstrate movement, where the feeling of something happening dominates. They appear as harsh in regards to contrast, dynamism of colors, and blurriness of content. The intent of generating neural network images of climate change is not to articulate a precise atmosphere. Atmosphere by definition is often beyond means of verbal articulation which is why I emphasize film and images in my approaches. However, the set of generated images is useful as a tool which allows for underlying aspects of images made by humans and influential on atmospheric construction to become observable. Subtle elements indicative of a constructed way of seeing, through emphasizing a particular atmosphere, are rendered visible.

References

Deleuze, Gilles and Félix Guattari. 1987. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated by Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Goodfellow, Ian, Jean Pouget-Abadie, Mehdi Mirza, Bing Xu, David Warde-Farley, Sherjil Ozair, Aaron Courville, and Yoshua; Bengio. 2014.

“Generative Adversarial Networks.” in Proceedings of the International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 2014), p. 2672–2680.

Peirce, Charles Sanders. 1991. Peirce on Signs: Writings on Semiotic, edited by James Hoopes. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.