Principles for Harmony

Inger Nordangård

for #V. ugly housing/housing aesthetics

Differens Magazine, summer 24

”Principer för harmoni” was originally published in Swedish on the webpage Arkitekturupproret.se, 2017: https://www.arkitekturupproret.se/2017/03/12/principer-for-harmoni/

Harmony and beauty are words that have become more or less taboo in Sweden, except in fashion and advertising. When discussing architecture, modernist architects have decided to ban expressions such as “beautiful architecture” and replace it with the concept of “good architecture”. So, talking about harmony in this context has become heretical, but we don’t mind being heretics.

Architects, politicians, and property developers, who for ideological or economic reasons have embraced modernist philosophy and postmodernist relativism, keep insisting that there are no rules and that beauty is something purely subjective.

However, most of us probably agree that there are more or less successful ways of combining materials, colours, and shapes, just as with tones, scents, and flavours. Chefs create recipes for successful combinations of flavours and textures and we have an innate instinct against eating food that tastes bad. We have harmony in music theory and we immediately recognise a sour note. Most people spontaneously prefer music based on the classical scale and harmonic chords, whether the genre is classical, folk, pop, or rock. Why would such universal preferences not also apply to the visual and spatial?

Professor Nikos A. Salingaros, mathematician, urbanist, and architectural theorist at the University of Texas, San Antonio, has attempted to define harmony in architecture in mathematical terms. He has in turn collaborated with and been inspired by the great architect and design theorist Christopher Alexander (1936–2022). Here follows a summary of Salingaros’ deeper analysis of the concept of harmony.

The Golden Rectangle

It has long been assumed that a rectangle with Golden Section (Golden Mean or Golden Ratio) proportions (approximately 1.618) is the optimal shape for creating harmony. However, as professor Salingaros explains in his essay “Applications of the Golden Mean to Architecture”, this has been disproved in various studies. It takes more than that to create an attractive building.

Minimalism focuses one’s attention on a single mathematical relationship — the rectangle’s aspect ratio. The Golden Mean became popular among modernist architects as one of the few techniques left, as they tried desperately to make their empty rectangular slabs likeable. Seizing on its mythical attractiveness, they thought that the Golden Mean could save them after they had eliminated all emotionally connective architectural components. – Nikos Salingaros

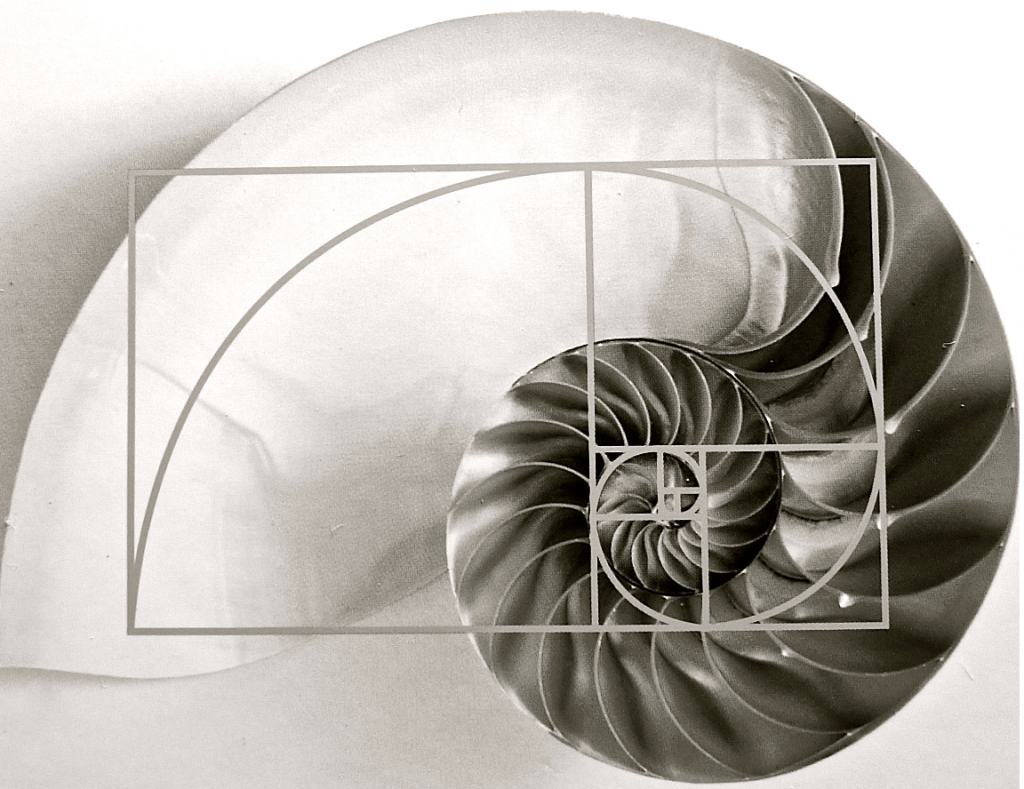

The harmony that the Golden Mean can achieve is thus not the rectangle itself, but rather the fractal scale within it; the Fibonacci sequence (1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144 etc).This can be found in the growth patterns and proportions of both plants and animals. Cross-sections of the nautilus shell is often used as an example.

IMAGES: Fibonacci Spiral in a nautilus shell (source: The Marmot, Flickr, CC2.0) Fibonacci Spiral in a Golden Rectangle (source: Wikimedia, public domain)

Salingaros advocates the same continuous scaling that we find in nature for creating harmonious buildings. That is, smaller and smaller details, right down to the grain size of the surface material. No part of the scale should be missing. This is how buildings were built before the advent of modernism.

Coherent hierarchical structures are found throughout historical and vernacular architectures, but are almost entirely absent from the formal architecture of the 20th and 21st centuries. A return to more life-enhancing buildings and urban spaces can well use this design method coming from natural growth and complex systems. Scaling in an ordered hierarchy of sizes receives support from the widely-found occurrences of the Golden Mean in natural systems (Livio, 2003). – Nikos Salingaros

IMAGE: Examples of harmonious grandeur with fractal scaling in the Sports Palace (1930) and the St. Erik’s Palace (1910) in Stockholm (photo: I99pema, Wikimedia, CC3.0)

Structured Variation

In his article “Why Monotonous Repetition is Unsatisfying”, professor Salingaros discusses other important aspects for creating harmony, such as structured variation.

We know from observation that human beings crave structured variation and complex spatial rhythms around them, but not randomness. Monotonous regularity is perceived as alien, with reactions ranging from boredom to alarm. Traditional architecture focuses on producing structured variation within a multiplicity of symmetries. Contemporary architecture, on the other hand, advocates and builds structures at those two extremes: either random forms, or monotonously repetitive ones. – Nikos Salingaros

The reason why humans neurologically react so negatively is not known for certain, but according to the biophilia hypothesis, our nervous system has evolved in environments that had a particular kind of cohesive, fractal, hierarchical complexity. When we find ourselves in minimalist environments, i.e. with opposite geometric properties such as emptiness or monotonous repetition, we tend to feel uncomfortable. According to Salingaros, this has been verified in various experiments (“Biophilic Design” by Stephen Kellert et al.)

Where in nature is monotonous repetition found on a large scale? Nowhere. Only at invisible atomic and microscopic levels can it be found in some rare pure crystals. Salingaros points out that even some of the most regular patterns in nature – the hexagons in a honeycomb and in the solidified lava flows of the Giant’s Causeway – contain irregularities that provide variety. Simplistically perfect and monotonous repetitive geometry simply did not exist before industrialisation, in the natural nor in the built environment.

To avoid monotony, Salingaros specifically recommends three of Christopher Alexander’s 15 principles:

- Levels of scale proposes that structure should contain a hierarchy of different scales, placed so that the factor between two successive scales is ≈ 3 (ideally 2.718).

- Alternating repetition suggests that simple modules should not be repeated, but be paired and interspersed with contrasting modules.

- Gradients can break monotony by making all parts in different sizes, with gradually smaller and smaller units.

Blending into the background and emotional nourishment

The currently so fashionable trend of contrasting and sticking out has no value in itself – except for the architect or developer seeking attention for their creation at any cost. For the rest of us, sticking out only creates disharmony, chaos, and stress. Salingaros explains why:

Natural environments are characterized by an enormous degree of structural complexity, yet for the most part, we perceive them as background.

Referring to Andrew Crompton, Salingaros points out that:

Human creations are designed either as neutral or picturesque, and traditional products are designed to vanish into our surroundings. When we inhabit an environment, or surround ourselves with human-made objects, we don’t want any individual object to bother us.

One reason for this, according to Salingaros, is that our perception is primed to notice and react to things that contrast against the natural background as that could be a sign of danger:

It signals alarm and makes us uneasy. Since natural environments are fractal, it follows that non-fractal objects will stick out and be noticed by us. This includes pure Platonic forms (cubes, rectangular prisms, pyramids, spheres) that define just a single scale, the largest one.

Unnaturally geometric or repetitive buildings or building elements may be easy to design and build, but they intrude on our attention by not blending into the background. They do not contain natural scale factors and therefore do not fit into a city that has evolved over generations. They stand out and cause us to react to them as if to a threat.

For comparison, consider colours. Most colours in nature are relatively muted. Together create a restful composition, even though there are countless hues, shades, tones and complex forms. Against this harmonious background, small accents of colourful flowers, fruits, and berries stand out to signal edibility or toxicity. Larger structures in bright, saturated colours does not occur in nature. Therefore, a lipstick red apartment building is not a refreshing splash of colour, but something clearly threatening – especially if it is large with sharp angles and randomly positioned architectural elements.

IMAGE: Kv. Muddus, Norra Djurgården, Wingårdh Arkitekter, 2017 (photo: Arild Vågen, Wikimedia, CC4.0)

Monotony or Chaos?

In order to break up the monotony of minimalist boxes, with their unnaturally smooth façades and rows of uniform windows, contemporary neo-modernist architects may try to create variation by introducing randomly placed and sized windows or balconies, façade panels in random colours, and other playful novelties. This adds to costs and construction difficulties with no gain other than sticking out. The end result is often chaotic and imbalanced. The reaction from the general public is generally negative because our bodies react to this randomness as to danger.

In this ever-escalating race for architectural drama, it gets even worse when contemporary deconstructivists design anonymous megastructures with hidden entrances, confusing grids, broken-up structures, or outward-leaning walls that give the impression of buildings about to melt or topple. Such shapes are not exactly conducive to a sense of safety and harmony. Read more about deconstructivism in Salingaros book Anti-Architecture and Deconstruction (2014).

In his 1980 classic Farväl till funktionalismen! (Farewell to Functionalism!), Swedish architect and teacher Hans Asplund (1921–1994) also analysed in detail what went wrong with modernist architecture and came to similar conclusions; that both repetitive monotony and random chaos are two extremes that do not make for good architecture. At one end there is too little variation and at the other there is too much. Cosmos is the term Asplund used for that middle ground between Monotony and Chaos, which Salingaros calls “structured variation”. Just like Christopher Alexander and professor Salingaros, Asplund also presents many useful tables, graphs and images to illustrate principles of harmony and disharmony in architecture. An updated version of Asplund’s book (in Swedish) was published in 2022.

With all this information, which is increasingly being confirmed by modern neuroscience, a good architect should be able to create both harmony and variety – and even grandeur when appropriate – without resorting to the most juvenile antics to attract attention. The knowledge of how to build comfortable, beautiful, and functional environments exists and has existed for centuries, even millennia. These principles can easily be applied to modern buildings. This is being done all over the world and, hopefully, a paradigm shift may be underway.

References

Salingaros, Nikos. 2012. Applications of the Golden Mean to Architecture.

Stephen Kellert et al. 2008. Biophilic Design. The Theory, Science and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life.