Some Reflections

with Kåre Frang

for #V. ugly housing/housing aesthetics

Differens Magazine, summer 24

For Differens Magazine issue #v. ugly housing / housing aesthetics, we are very excited to present works of visual artist Kåre Frang, a graduate of the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts (2020). Frang’s artistry, primarily in video and sculpture, often merges these mediums within staged environments to explore themes of change and everyday life fragility. His works are characterized by the distortion and transformation of familiar objects like children’s games and toys, evoking a sense of estrangement or unease in the viewer, while also exploring notions of shelter, housing, and homes examining how these things—and our interactions with them—transform and hold under various pressures.

Frang’s accolades include the 15. Juni Fondens Hæderslegat, the Carl Nielsen og Anne Marie Carl Nielsen talent award, and the Silkeborg Kunstnerlegat. His exhibitions span prestigious venues and festivals across Denmark and internationally, such as Kunsthal Charlottenborg, The Nivaagaard Collection, Den Frie Udstillingsbygning, CPH:DOX film festival, and Ruttkowski; 68 in Paris. Notably, his solo exhibitions, like Bake a Cake and Landscapes of Doubt, showcase his ability to juxtapose past and future, evoking both nostalgia and a subtle dystopian unease.

Besides exhibiting his artworks within this issue, we have had the great opportunity to discuss some of them in detail in what follows.

Differens: In ‘Head-in-the-sand’, three houses are partially buried in sand in one picture, and drowned in water in the next, as if the water level had risen drastically. To us, this work reflects fragility and instability, both in nature and environment, as well as in culture and buildings. What do you think stability means for thinking about something like homes? What is the imagination of an unstable home? When do you consider a home stable and when is that stability threatened? What happens to the sense of home when the surrounding world behaves unpredictable? You have chosen to use traditional half-timbered houses and to set up this apocalyptic scenario in Denmark – is there a specific reason for that other than that it is an environment familiar to you?

Kåre Frang: The work ‘Head-in-the-sand’ was never planned to be flooded in the ocean, but three weeks after the opening of the exhibition a very strong storm surge surprised us all with a sudden de-installment of most of the works. To me, it was both beautiful and scary. The work, consisting of a half-buried upscaled version of a wooden toy farm with a toy rhinoceros partly hiding under its roof, was dealing with the biodiversity- and climate crisis. At first it felt almost as if the conversations about various crises and future challenges only took place on a fictional level, and therefore it was a gift when abstraction was overtaken by realityand became a part of the work while also amplifying the seriousness of the conversations already taking place within the work.

I am occupied with changes and transitions in various forms and contexts. I think that both on a personal level and as a society, the more transitions we’ve been through and the more recent they are – the more open to changes or vulnerable to a state of instability we become. My focus is not really on buildings or architecture, it’s more about what sheltering means to us – both as a home and in how we deal with issues in general. The roof stands to me as a strong image of dealing with the unpredictable, and I appreciate the simple logic of moving and burning a material from our ground with the purpose of keeping us dry above the ground.

‘Head-in-the-sand’ was installed on the beach of the Nationalpark Wadden Sea, a very special place in Denmark with lots of history. One of the stories I discovered in my research, was how around 150 properties were expropriated by the Danish state between 1964 and 1971, simply to increase our military area in order to meet the criteria for being accepted as a member of NATO. I found the story interesting as an example of how it was possible for the state to take action and make sudden non-popular decisions, if they found the cause important enough. I wanted to refer to the act of making decisions, especially when dealing with other crises than war. The title therefore had to be ‘Head-in-the-sand’, as in being unwilling to recognize or acknowledge a problem or situation.

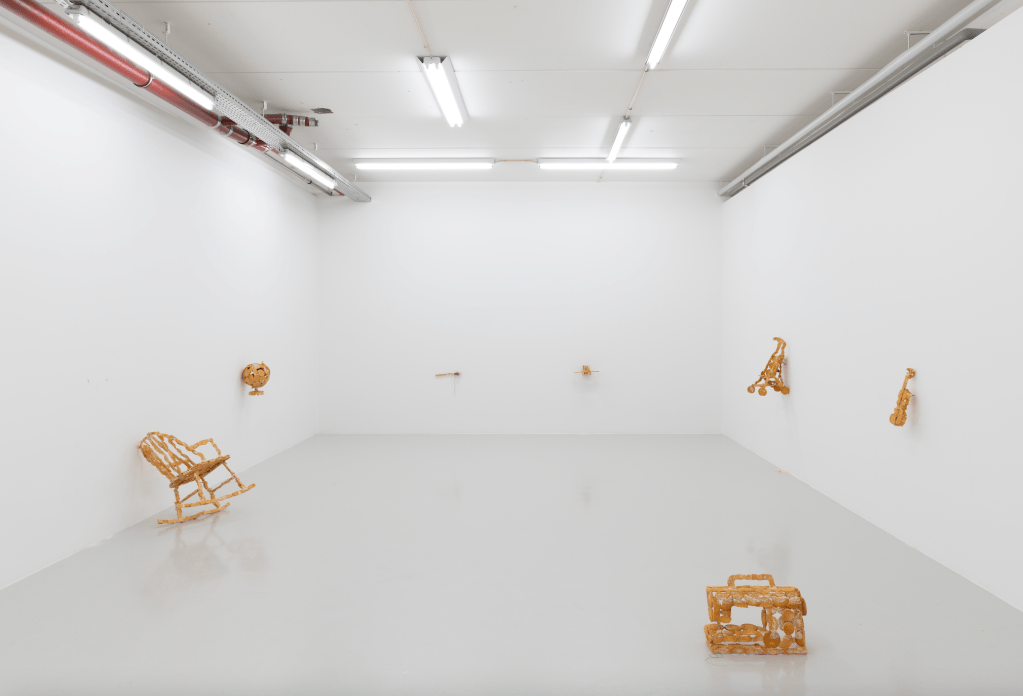

Differens: Like ‘Head-in-the sand’, ‘Attachment’, ‘Привързаности’, and ‘Chart in Tivoli’ seem to discuss a fear of instability, but also of disuse, and the failure of construction and building. It shows collapsing or non-functional constructions and highlights moments of failure in an attempt to form and maintain stability. The works also seem to be about sustainability and technical perfection, particularly in engineering, historically associated with technical principles for bridge building, where in these works, the technique and result often falls short, being unsustainable and inviting thoughts of impermanence and unsafety. As such, we also understood these works to be contemplating engineering and technical problem-solving, highlighting our hopes and expectations on design and architecture to provide us with technical solutions. The work humorously suggests that these solutions often fall short of perfection, creating a disconnect and prompting reflection on our trust in what such solutions have to offer. The work can as such be seen as a critique of the prevalent expectations that design, architecture, and engineering alone can solve complex crises facing modern society.

The biscuits, used as material in the works, suggest a lack of adult oversight in construction endeavors and seem to question the idea that society as a whole is mature and capable of understanding the underlying complexities – such as contextual instabilities and changes – in construction projects and problem-solving. What inspired you to use biscuits as medium within these works, and what message do you hope viewers take away from it?

Kåre Frang: During the big COVID lockdown, I was spending many days in my studio with my son who was six years old at the time. As a rule, we agreed that we had to make “art-work” only while being in the studio. Whatever that is. We started off with the more traditional approaches such as sculptures of clay and painting on canvas, but as days went by – it felt like none of us got any closer to an answer when it came to what art is to us. At one point, when the restless energy was at a peak, I simply said: We don’t have to do it like this, we can basically make anything out of anything, what about if we go to the supermarket and buy lots of something and create out of that? His immediate response was: Let’s buy a lot of biscuits. Of course that was also an outburst driven by his wish to eat them but that same day made a horse carriage that was dragged by a car of biscuits and hotmelt glue.

Months later, I was still very attracted to the whole energy that suddenly evoked while doing something that in the moment felt purposeful, and I was seeking reasons to create a full show only with biscuit sculptures. I just didn’t know why and where the attraction came from, since biscuits weren’t that interesting to me. At first I dug down into the story behind the biscuits. There was a fun and interesting story behind the digestive biscuits, but it felt more as a bonus element than a purpose to use them. Then I started to make small horse carriages out of biscuits but they all started to dissolve and fall apart as a result of the studios moist seeking into the biscuit, and at that point I understood what potential they had as a continuation of previous interests of mine in decay, transitions and collapses.

I then decided to build the exhibition up around the fact that I was doing my first solo exhibition in a commercial gallery. The core purpose of the works in that context was a shift in ownership and I wanted to put focus on how we attach to our belongings as if they were a part of ourselves, as victims of natural disasters often describe the feeling of loss of their homes.

Practically I decided to make the necessary work it took to preserve the sculptures and keep them in a state where they visually wouldn’t move or change over time. This was done by casting and handpainting each piece of biscuit used in the work, then after they were glued together as imitations of objects that I have a personal attachment to. The items selected were also representatives of various categories of things we collect often with no other purpose than storing them till our end.

As with many other of my works, these works take their departure from a very personal place but with the intention to create something others can use as a starting point of a new line of thoughts. I hope that visitors felt like they were looking at things soon to fall apart, since the idea of catching a crumbling or dissolving world full of things, resonated well with how I was experiencing many things at the time.

The collapse was both present and yet only a staged glimpse before falling apart.

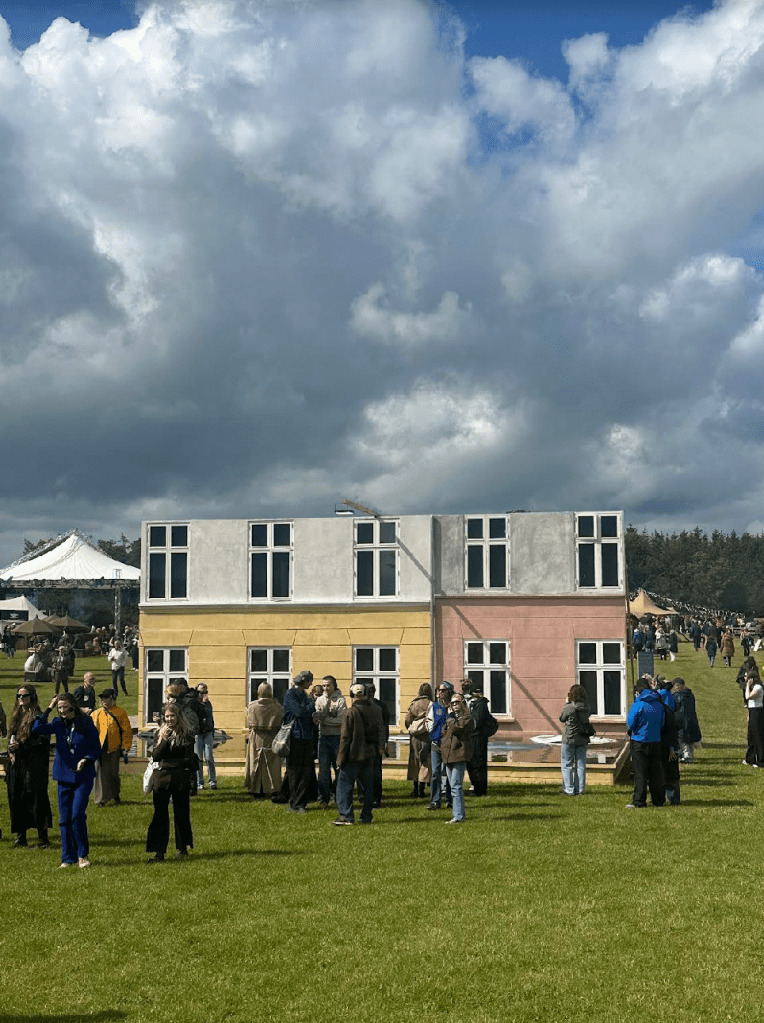

Differens: For the work ‘Overwhelmed’, we discussed different notions of flooding and discovered both literal and metaphorical meanings to possibly discuss more. Most interestingly in the discussion among the editors, we always ended up in the conflict between the flood and human attempts at planning and fixing existence. The text suggests that the work revolves around a nightmare scenario of cities and homes succumbing to floods while also calling for association to the inner flood of overwhelming emotions. We thought about our own attempts to plan and structure our everyday life, which many times ends in a collapse of plans and structure as something unexpected happens or overwhelms us. We also thought about the present self-help culture and trends of taking action towards “managing” everyday life with “healthy routines” and such, and about how this faith in planning really has increased with increasing threats of different crises. The concept of being overwhelmed transcends mere incapacity; it embodies the collapse of meticulously laid plans in the face of an overpowering force. It speaks to our attempts to impose principles and rules, only to be thwarted by the immutable forces of nature or unforeseen circumstances.

We thought that the placement of the artwork on a table evokes a sense of consumption, as if we are ingesting that which both destroys and protects us. “Putting something on the table” is also a way of making it a part of our agenda and we thought, with this reference, that the placement of the table as such symbolizes our often times high awareness (in treating it as a part of an agenda) of a coming crisis at the same time as our desire to quickly settle with any plan in times of uncertainty, perhaps demanding us to wait and understand the crises. This desire – perhaps a planning impulse or impulse to move forward with a plan – could be seen as a consumption not only of affects of planning, such as agency, control and power, but also of resources that we, in our haste to plan, do not understand lead to new harrowing scenarios.

The city emerges as a focal point where human culture clashes with nature’s flooding and overwhelming force. The table becomes a locus of planning, sketching, and decision-making, contrasted against the sudden chaos of an unplanned flood scenario. Despite our awareness of these impending disasters, we struggle to manage the deluge, highlighting the inadequacy of our actions and the illusion of control. Displayed in an open space, basking in the sunlight, ‘Overwhelmed’ beckons all who pass by. We understand it as a reminder of how short-sighted planning, epitomized by it’s location – the parking spaces for cars which was emblematic of the hasty urban planning of the 1960s car-centric society-, give rise to new unexpected futures and unforeseeable scenarios.

Kåre Frang: I am deeply thankful of how you’ve reflected on this work, since it is a very special work to me. Hopefully, the work will someday resurrect in its attempted form – as a fountain of painted bronze in a public space.

The work ‘Overwhelmed’ is both a 1:1 sketch model for a fountain made of cast and hand-painted bronze and a work in itself. The work both deals with the nightmare scenario where cities and homes are flooded, but also to how we as humans can feel overwhelmed in a way that is best described as an inner flood that drowns our ability to think clearly. I imagine ‘Overwhelmed’ to be realized as a fountain in public space, with the entire sketch including table and chairs cast in bronze, which will then be hand-painted naturalistically. The water will constantly flow out from under the cars, and flow over the city, the table and the chairs and splashing onto the ground, and pumped up again. All at once we’re flooded and overwhelmed.

Among the works displayed on Differens Magazine’s website within the issue #v. ugly housing / housing aesthetics, are ‘Head-in-the-sand’, ‘Attachment’, ‘Привързаности’, ‘Chart in Tivoli’, ‘

Det bliver mørkt om natten’, ‘Overwhelmed’, and ‘Loving Eyes’. To read more about Kåre Frang’s art, or about any particular work, visit his website: https://kaarefrang.eu/

or instagram kaare_frang for updates.