The Female Gaze

Excerpt from Testosteron, published by Atlas 2024

Selma Brodrej

Differens Magazine, autumn 24

When I think of the male body, I first think of an ancient statue. A hard and cold surface, a modest sex and a perfect chest. It is a body that is impenetrable, you can touch it, lean your head against it, kiss it on the chest, but you can never get to it.

The other thing I think about is a father’s body. The father’s body is safe and strong, but the strength is not visible. It is hidden behind a soft layer caused by a childish love of sugar and a tiredness of life compensated by a few too many beers after work.

In the big man’s lack of self-control there is something vulnerable and lovable. Perhaps this explains why the term “dad bod” has been trending and portrayed as something sexy on social media in recent years, not least after a couple of paparazzi shots of a chubby Leonardo DiCaprio by the sea. As I am scrolling through the Google feed of dad bodies, I find the Time article “‘Dad Bod’ Is a Sexist Atrocity” and get my hopes up. Initially, I believe that I have found a text that puts us women who objectify men in our place, but as I read on, I realise the article does the opposite. Brian Moylan writes:

“But just as the beauty standards for men were starting to get as stringent as they have always been for women, along comes the Dad Bod. Now all of our prospective Brad Pitts can look more like Seth Rogens. And while it might be nice to cuddle up to Seth Rogen, just look at his romantic partners in his movies. They certainly do not look like they stopped going to yoga class and let themselves get a little bit thicker than the day they graduated from college.”

There is a kind of injustice in the fact that women are still expected to be thin while men get away with being attractive regardless of whether they have a six-pack or a beer belly. But I am not sure sexism is the right term for it since there are other, less controllable, aspects of a man’s appearance that have at least as much impact as a woman’s BMI on his chances of being perceived as sexy.

Kris Lemsalu, One foot in the gravy, 2024, photo by Piere Le Hors.

The most obvious example is height. If you’re male and under 170 centimetres, you are going to have a hard time on a dating scene, not least online where many girls bluntly state that they are not interested in short guys. And if you are short, neither diets nor yoga will help you. Another such aspect is hair growth. Male pattern baldness is common and causes great anxiety among men. Many are affected as early as in their 20s and are forced to either shave their hair or pay large sums for hair transplants, often with half-assed results. And while a high hairline or bald spot is not a dealbreaker for most, it is another example of how men, like women, are affected by the way they look.

If you’re male and under 170 centimetres, you are going to have a hard time on a dating scene, not least online where many girls bluntly state that they are not interested in short guys. And if you are short, neither diets nor yoga will help you.

The editorial writer Susanna Kierkegaard wrote an article on the subject in Aftonbladet in February 2023. In the article, Kierkegaard makes fun of the thin-haired men by writing that it is not only they who suffer from their hair loss but that “thinning hair brings a lot of suffering to us spectators as well”. In the same text, she explains how she, as a woman, is influenced by beauty ideals, and argues that there is a kind of justice in the fact that men also feel bad because of how they look: “In a way it feels fair. I have spent a lot of money on eye shadows and hair masks to try to look nice. You scrub, paint your nails and squeeze into uncomfortable clothes.”

The text fascinated me for several reasons. Firstly, because it pulsates with an explicit misandry that is rarely encountered today, but was all the more common ten years ago. Kierkegaard mocks a widespread male insecurity in a manner devoid of empathy, thereby dehumanising their experience. By comparing the thin-haired men to figures like Homer Simpson, and a freshly boiled egg, Kierkegaard distances herself from the men and places herself above them.

Kris Lemsalu, V from VITA, 2024, photo by Piere Le Hors.

But what particularly struck me about the article was the naive conclusion she reaches. Kierkegaard’s encouragement to the men was that they should accept the hair loss. “It is not so bad to have less hair on your head, you can still have a nice haircut. Let the hair follicles go into hibernation, stop fighting it.”

Why she, and all the other women who spend money on eyeshadows and squeeze into tight clothes, do not follow the same advice remains unsaid. It is not so bad to be a little ugly, stop fighting it, I wanted to tell her.

By comparing the thin-haired men to figures like Homer Simpson, and a freshly boiled egg, Kierkegaard distances herself from the men and places herself above them.

The problem with beauty ideals is that we live in an age obsessed with surface. Dismissing complexes as irrational, or encouraging people to “stop fighting it”, is therefore rarely constructive. It is depressing, but impossible to deny, that society favours beauty. Most people agree that this favouritism makes it difficult for women who do not achieve the ideals, but when it comes to men, the issue seems to be more controversial.

In the chapter “The world hates ugly women”, from the author Tone Schunnesson’s anthology Tone tur och retur, Schunnesson writes about her conflicted feelings towards cosmetic surgery. She describes how, one day when she is sad and bored, she makes an appointment to inject fillers, which she then cancels. When she receives confirmation that the appointment is cancelled, she first feels a small sense of victory, as if she has listened to her body’s resistance. But then she begins to wonder if the cancellation itself is not also a result of vanity, since a pair of full lips would signal that she “carries the self-hatred that all shallow, stupid women carry”.

Schunnesson succeeds in accurately depicting the double bind of being a woman who is not naturally beautiful according to the prevailing ideals. “We can choose between the shame of giving in and the world’s hatred of ugly women,” she writes, and perhaps hatred is an unnecessarily strong word in this context. But pick up any daily newspaper and look at the byline pictures of the female writers, turn on the TV or go to the publishers’ author portraits. It’s hard to find a woman in the public eye who does not look good, and I find that the same tendency has increasingly spread to men.

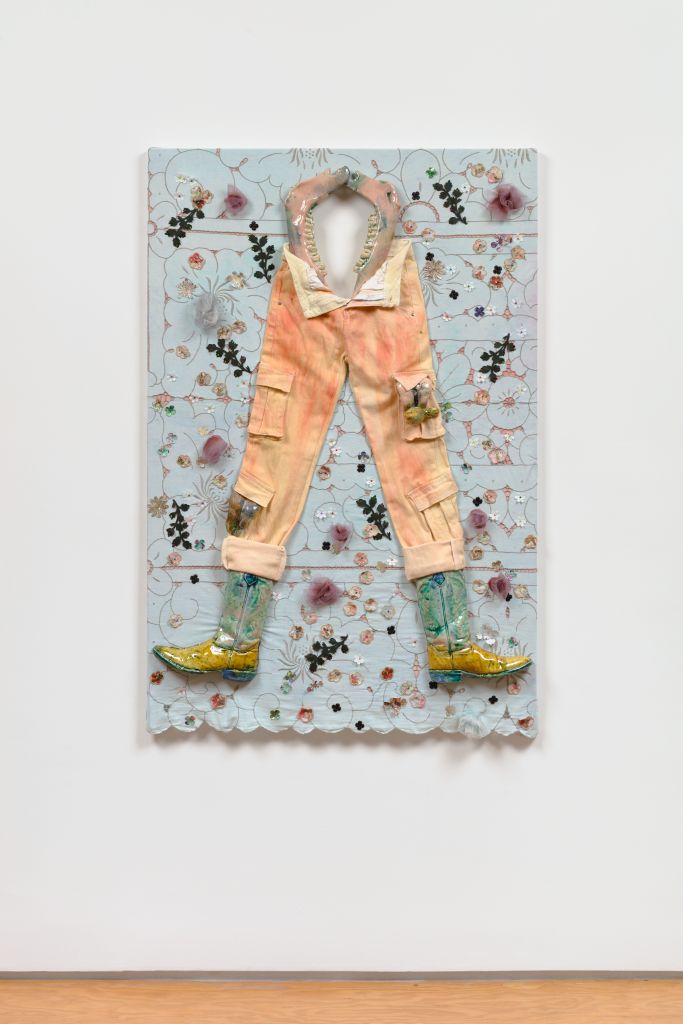

Kris Lemsalu, Hubby, 2024, photo by Matthew Sherman.

In 1973, British film theorist Laura Mulvey coined the term “the male gaze”. In an essay entitled Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, Mulvey broke down the mechanisms of cinema to try to reveal how cinematic conventions are built to reinforce a patriarchal fantasy. When we watch movies, we see what the camera wants us to see, and according to Mulvey, the camera often wants us to see posing female bodies that are not necessarily shown to advance the narrative, but often only to decorate it. Her thesis could also be summarised in the words of John Berger from his book Ways of seeing: “Men act, women appear.”

Mulvey went on to explain that the world of cinema does not operate in a vacuum, but is governed by the laws that produced it, that is, what we see on screen is a result of the society and times we live in. According to Mulvey, it was no coincidence that films tended to depict gender roles from a patriarchal perspective, with a classic division between passive femininity and active masculinity. It was an accurate reflection of the world in which the films were produced.

50 years later, the male gaze is still present, although often more subtle. We have more film directors who have learned that a stripped, attractive female body that only decorates is associated with a slap on the wrist. A pronounced use of the male gaze has become so uncommon that it was refreshing to see Sam Levinson and Abel Tesfaye’s (The Weeknd) HBO series The Idol, where probably half the scenes showed Lily-Rose Depp naked.

50 years later, the male gaze is still present, although often more subtle. We have more film directors who have learned that a stripped, attractive female body that only decorates is associated with a slap on the wrist.

There was something outdated and cheeky about the show’s imagery, which unapologetically zoomed in on a butt or a pair of breasts time and time again. But The Idol was also slammed in most major media for exactly the same reason.

While the way the female body is portrayed in film has changed in part, new forms of expression have emerged since 1973. On social media, we are in many ways our own directors, in control of how we portray ourselves, and on these platforms many women use their bodies to decorate rather than “advance the narrative”.

Kris Lemsalu, A from VITA, 2024, photo by Piere Le Hors.

The last decade has been marked by wild debates about whether these decorations should be categorised as internalised sexism, where the male gaze has crept into women and controls them even when they are superficially acting independently, or whether it is, on the contrary, a reclaiming of power, as women used to be forced to pose but now do so voluntarily.

Personally, I think it’s difficult to talk about anything that happens online in terms of free will. Whether the goal is to appear sexy, unashamed, funny or healthy, everyone who participates in the strange social media circus is a slave to it.

Laura Mulvey argues in her essay that the female appearance is “coded for strong visual and erotic impact” and that women can thus be said to “connote to-be-looked-at-ness”. She goes on to argue that the male cannot bear the burden of sexual objectification, at least not “according to the principles of the ruling ideology and the physical structures that back it up”.

But today we see that men too, and not just male actors or performers, bear the burden of sexual objectification. They, like women of all times, have started to show themselves to satisfy a viewer. On social media, many men post material that suggests that they, like women, now “connote to-be-looked-at-ness”. This can be anything from exercise photos to Tiktok dances, the common thread is that the men do this performatively and with an ambition to receive female validation, which they often do.

But today we see that men too, and not just male actors or performers, bear the burden of sexual objectification. They, like women of all times, have started to show themselves to satisfy a viewer.

This is most evident in the online romantic market. In her book The New Laws of Love, sociologist Marie Bergström explains that online dating contributes to an increase in female agency: “Where women are generally regarded as mere sexual objects—the object of male desire—online dating is part of the historical transformation of women into sexual subjects.”

This, while fundamentally a positive development, unfortunately seems inevitably to come at the expense of men becoming increasingly objectified. Bergström describes this as a new experience, at least for heterosexual men, while there has long been an established sexualization of the male body in the gay community.

“Men pose for pictures and try to look good and sexy to attract the female gaze. In turn, women browse through profiles and enjoy looking at men. Online dating has not erased the gender inequality that makes women much more vulnerable to beauty ideals and sexual objectification. However, it does familiarise men with the experience of being evaluated and the self-consciousness that comes with it, and women with being the subjects of observation”, Bergström writes.

On these platforms, run by international corporations that profit from our loneliness and thirst for validation, men are forced to experience what it feels like to be the passive, watched one (the woman) while women get to try out the role of the active viewer (the man).

Since there is no evidence that this has made women less sexualized, it can be seen as an example of when misguided feminism and greedy capitalism interact and lead to the worst version of gender equality: Men and women behaving and feeling equally bad, or at least coming closer to doing so.

Anyone who disagrees with me could argue that it is bizarre to compare several centuries of both figurative and literal corsets to a single small decade of being objectified online. When I talk about the difficulties men face, I often hear such arguments, and I’m not sure how relevant they are. Should we allow a problem to escalate before discussing it, just because it will be more fair?

Kris Lemsalu, T from VITA, 2024, photo by Piere Le Hors.

The women’s movement has long highlighted women as a group. It started with the idea that we could talk about common female experiences, which led to creating well-established concepts like sexism and objectification. It has been necessary for women to organise themselves to be listened to. If they had not talked to each other and created contexts where they could build a movement together, feminism would probably never have existed.

Men, on the other hand, have avoided talking about themselves in general terms and instead emphasised what distinguishes the male individual from the male group. Many people make fun of the phrase “not all men” and link it to an easily offended type of man, but there is actually some justification for this type of formulation. When men are discussed as a group, it is usually about destructive tendencies that many people, for good reasons, do not want to be associated with.

It is as if men have too much to lose by coming together, that the risk of someone in a male group carrying something the others do not want to be associated with still feels imminent and that they therefore, to a much greater extent than women, avoid organising. I know that there are many exceptions and that figures like Andrew Tate and Jordan B Peterson should not be forgotten in this context. They definitely play an important role and have really managed to mobilise people to get involved in men’s rights. But since many people perceive these figures as extreme, right-wing and more or less criminal, they are also dismissed by a large number of men. And the men who reject them hardly start their own men’s movements. Quite the contrary.

It is as if Tate, Peterson and a number of similar characters have set the tone for men’s rights activism in a way that has basically given them a monopoly on it and made us associate it with something suspicious and violent.

For something to be perceived as a systemic problem, it needs to be articulated on systematic grounds. Men find it difficult to create these grounds and, on the few occasions when they do, tend to shake them by making violent tendencies or clumsy statements overshadow what should be the foundations of the movement.

So there is reason to wonder whether some of the problems associated with being a man today are perceived as individual when in fact they are common.

I hope that men will become better at organising themselves and that they, when they do, receive a more dignified treatment. They should not have to hear arguments that belittle their struggles, and they should not be encouraged to stop fighting it.

Excerpt from Testosteron, published by Atlas 2024. Used by permission.

Selma Brodrej

Selma Brodrej is a cultural journalist at the Swedish newspaper Dagens ETC. The essay collection Testosteron, published by Atlas 2024, is her debut.

References

Berger, John. Ways of Seeing. London: Penguin Books. 1972.

Kierkegaard, Susanna. ”Livet är inte över bara för att du blivit flintis”. Aftonbladet. 2023.

Levinson, Sam. The Idol (TV series). 2023.

Moylan, Brian. ”Dad Bod is a Sexist Atrocity”. Time. 2015.

Mulvey, Laura. ”Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”. Screen, Volume 16, Issue 3, Autumn 1975, Pages 6–18.

Schunnesson, Tone. Tone tur och retur. Stockholm: Nordstedts. 2022.

Bergström, Marie. The New Laws of Love: Online Dating and the Privatization of Intimacy. Cambridge: Bristol University Press. 2022.