Transforming the Terrifying:

Fascist Aesthetics Then and Now

Mathilde Lyons

Differens Magazine, autumn 24

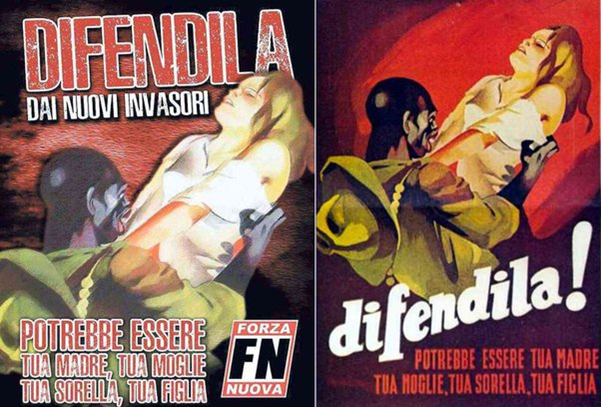

Left: Forza Nuova poster from 2017 reading ‘Defend her from the new invaders’. Right: Gino Boccasile’s 1944 poster, reading ‘Defend her! She could be your mother, wife, sister or daughter’.

In 2017, Italian neo-fascist group Forza Nuova revived a 1944 propaganda poster to stoke fears against immigrants, demonstrating an unsettling continuity that underpins the enduring legacy of fascist ideology. The poster, originally designed by the artist Gino Boccasile, read ‘Defend her! She could be your mother, wife, sister, or daughter.’ Recognising the reclamation of fascist era symbolism and narratives is essential to explore how fascist ideology in Italy has evolved from the colonial and imperial politics of Mussolini to become embedded in contemporary far-right politics; illustrating the persistent influence of racial and nationalist myths. This essay examines the development of fascist aesthetics in Italy from its origins in the early 20th century to its resurgence in modern times.

Making Italy

Walter Benjamin argued in his essay ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’ that fascism aestheticised politics, while communism should respond by politicising art. The forms this aestheticisation process took during the Italian fascist period were so omnipresent and diffuse that any discussion of the regime is inherently a discussion of the aesthetics, rituals and symbols of fascism. The cult of Mussolini meant, for example, that all school classrooms had a photo of him hanging up, setting himself up as a ubiquitous and pervasive figure whose presence could be seen as a reassuring figure for his followers and an ever-looming threat to those who considered defying the regime. The sheer power of the propaganda machine, such as the creation of the Luce Institute and Cinecittà, meant that the regime could produce newsreels and films that promulgated their message and defined a certain vision of what life should look like.

The project of nation-building requires a national myth. In the case of Fascist Italy, this myth came in the form of a celebration of the glory of Ancient Rome, or Romanità (Roman-ness) which Mussolini instantiated as an extreme form of nationalism. Georges Sorel regarded national myths as a source of rejuvenation that could be used by politicians to create a sense of shared history and values, and this appeal to nationalism during the Fascist period was a cornerstone of the drive to create a Fascist empire to rival that of Rome. Furthermore, Italy was not immune to the racial theories prevalent across Europe in the late nineteenth and early-twentieth century – Romanità was combined with the biological myth of racial purity in the regime’s effort to symbolically unify the nation. An example of this can be seen in the Stadio dei Marmi sports stadium in Rome, which was built in 1932 and is encircled by 60 white marble statues of naked athletes. The figures’ potent yet chaste athleticism was intended to symbolise an ideal form of fascist masculinity. The stillness of the statues stands in contrast to the dynamic landscape thousands of Italian men found themselves in in the 1930s, as the regime looked for ways to entice them to the colonies, appealing to both financial motivations and sexual desires, promising ‘exotic’ encounters with African women.

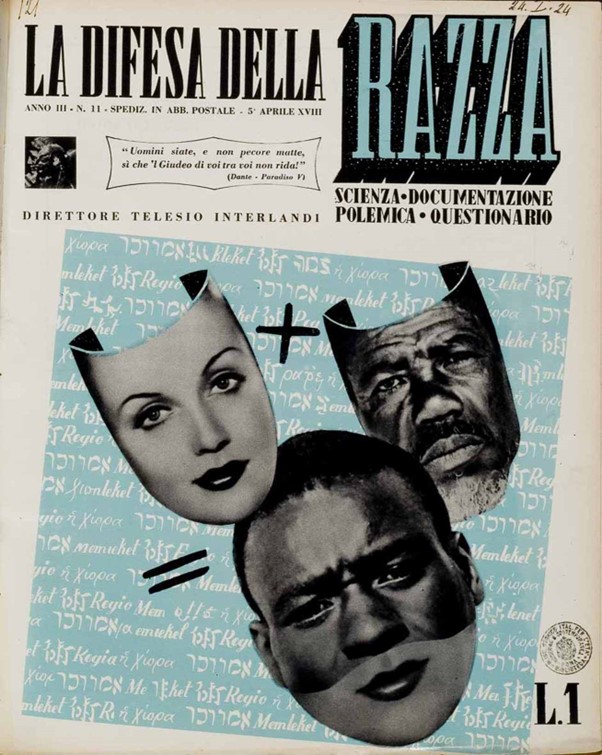

La difesa della razza cover 20/05/1940.

… the regime looked for ways to entice them to the colonies, appealing to both financial motivations and sexual desires, promising ‘exotic’ encounters with African women.

This nation-building project sought to ensure that the new Italy would be a white nation. Thus, the ‘whitening’ of the Italian nation involved creating an ‘Italianness’ in opposition to other Europeans’ perceptions of Italians, as well as in opposition to colonial subjects’ racial identity. Italian fascism had to confront and counter the views of German and French racial theorists who regarded Italians as a hybrid Afro-European race. Internal racial questions, like the identity of Southern Italians, required defining the self and identifying a racial Other to attempt to homogenise national identity. These forms of identity formation did not just act as a form of racialisation, they were also used to inform beauty projects by defining these Others in opposition to Italian beauty. African women were placed as a countertype to the Italian women who would reproduce a supposedly white and pure nation and thus give birth to future fascists.

Motherhood is war

Related to this, the cult of motherhood emerged during this time alongside the glorification of war. Women were expected to uphold biological duties by shedding blood for the nation in childbirth just as men shed blood through war. This is encapsulated in Mussolini’s belief that ‘War [is] to man what maternity [is] to a woman.’ The Futurist poet and fascist pioneer, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, expressed the sacralisation and aesthetic elevation of war. In response to the Italian invasion of Ethiopia in 1935, as quoted by Walter Benjamin, Marinetti put it this way:

”For twenty-seven years we Futurists have rebelled against the branding of war as anti-aesthetic […] Accordingly we state: […] War is beautiful because it establishes man’s dominion over the subjugated machinery by means of gas masks, terrifying megaphones, flame throwers, and small tanks. War is beautiful because it initiates the dreamt-of metallisation of the human body. War is beautiful because it enriches a flowering meadow with the fiery orchids of machine guns. War is beautiful because it combines the gunfire, the cannonades, the cease-fire, the scents, and the stench of putrefaction into a symphony. War is beautiful because it creates new architecture, like that of the big tanks, the geometrical formation flights, the smoke spirals from burning villages, and many others […] remember these principles of an aesthetics of war so that your struggle for a new literature and a new graphic art […] may be illuminated by them!”

Sintesi Fascista by Alessandro Bruschetti, 1935, Rights: The Wolfsonian–FIU, The Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection.

Maintaining ‘the stock’ and anti-miscegenation

Modernist visions of a new literature, a new art, and a new aesthetics combined with visions of a ‘new man’ in fascist thought. In that vein, Nordicist philosopher Julius Evola wrote that the theory of an Aryo-Roman race and its corresponding myth could support the Roman idea proposed by Fascism and provide a foundation for Mussolini’s plan to elevate the average Italian and to ‘enucleate in him a new man.’ Anthropologist Arturo Sabatini, in Il concetto della razza nell’etica fascista (1940), discussed changes in the Italian somatic type during the Ventennio, noting that Italian youth in the 1930s had grown taller and developed wider chests compared to previous generations. This argument reinforced anti-miscegenation sentiments, suggesting that such progress and aesthetic improvements in the Italian people could only occur when Italian biological greatness was not ‘polluted,’ implying that the regenerative quality of the ‘new man’ would yield both physical and spiritual results. The Fascist nation was conceived as a living organism, with individuals acting as cells, competing in a struggle for the ‘survival of the fittest.’ Mixed-race individuals were framed as alien bodies detrimental to the nation’s health and were to be considered an incongruous and polluting presence. Mussolini argued this point to his mistress Clara Petacci, claiming that large numbers of mixed-race births would ruin what was beautiful in Italians.

Mussolini’s obsession with maintaining both la stirpe (‘the stock’, the quality and prestige of the Italian race) and a high birth rate led to a Fascist preoccupation with the sexual habits of Italian citizens. Paolo Orano, a psychologist and leading figure within the National Fascist Party, advocated that the ‘celibate does not have a right to the honour of citizenship; he is inferior, lost, illegitimate… there is nothing more just and sacrosanct than the exclusion of celibates from work, as if they were people of a foreign race.’ The concern with birth rates and the maintenance of reproducing the correct new individuals were intimately intertwined and these related ideas lay at the core of the fascist project.

La difesa della razza cover 05/04/1940

The song Facetta Nera (‘Little Black Face’) was a rallying cry and promised Italian men that if they went to the colonies, they could bring beautiful Ethiopian women back to Rome as their wives. Ethiopian women are described in the song as a ‘slave among slaves’ to be kissed under the Italian sun. This song, alongside postcards depicting African women in degrading ways, through mocking cartoons or topless or nude photos, exemplified the colonial fantasy. Sexual control was not unique to Italian or Fascist era colonialism. The historian Ann Stoler points out that “more than a convenient metaphor for colonial domination”, it was a fundamental feature of the system.

Despite this, a few years after Facetta Nera had been used as the Italian anthem of colonisation, the regime adopted a staunchly anti-miscegenation position. There are several arguments made by historians as to why, and one of the most common views is that colonisation required a strict segregation between coloniser and colonised, and mixed-race children were very real evidence that interracial relations were occurring. There was still some tolerance of interracial sexual relations in the colonies, as long as African women were relegated to mere ‘outlets’ for sexual desire, as noted by a 1939 judicial ruling. The children of these relationships found themselves in complicated positions and their access to Italian citizenship became increasingly restricted throughout the 1930s. In 1940, a set of legal barriers were introduced that made it impossible for the child of an Italian man and an African woman to become an Italian citizen. However, those who had gained citizenship before 1940 were considered ‘Aryan.’ In his essay ‘Ur-Fascism’, Umberto Eco identified the syncretic nature of fascist ideology, which ‘must tolerate contradictions’, in this context allowing mixed-race individuals to be considered African or Aryan depending on the year they sought citizenship. Thus, a mixed-race person could be considered only African, or only Aryan Italian, depending on which year they applied for citizenship, a fact that speaks to fascism’s discomfort with those who do not fit neatly within the prescribed categories of identification and the image of homogeneity. The 1940 law stated that Black mixed-race people who were not citizens by 1940 would assume

”[…] the status of the native parent and he/she is considered native to all intents and purposes: he/she can no longer be recognised by the parent citizen, nor can he/she use the name of the parent. He/she must be maintained, educated, and instructed at the exclusive cost of the native parent. Institutes, schools, colleges, special boarding houses for mixed race children, even if of a conventional nature, are forbidden.”

The insistence on singular identity categories for individuals, as either African subjects or Italians, reflects a fundamental facet of fascist ideology. Robert O. Paxton provides a framework for understanding anti-miscegenation and racial science as integral components of the broader ideological foundations of fascism. ‘Fascism’, he writes,

”may be defined as a form of political behaviour marked by obsessive preoccupation with community decline, humiliation, or victimhood and by compensatory cults of unity, energy, and purity, in which a mass-based party of committed nationalist militants, working in uneasy but effective collaboration with traditional elites, abandons democratic liberties and pursues with redemptive violence and without ethical or legal restraints goals of internal cleansing and external expansion.”

Towards the end of the Second World War, with the arrival of Black American troops into Italy, the dynamics of miscegenation changed dramatically. No longer were Italian men exerting extensive colonial violence on African women in East Africa. Instead, white Italian women were the ones engaging in interracial relationships within the metropole. This was particularly noted in Livorno where the United States’ 92nd Infantry Division, also known as the Buffalo Soldiers, were stationed in the Tombolo forest from 1944. In his novel Educazione Criminale (‘Criminal Education’), Vito Bruschini wrote that ‘[i]n the early post-war years, Livorno was for the Italian people what Saigon was for the Vietnamese population during the conflict with the United States: the abyss of dishonour and the degradation of a nation.’ Tombolo occupied the obsessive post-war imagination of interracial relations in Italy, and the women who dated these soldiers or engaged in sex-work were dubbed segnorine, a derogatory neologism that played on American pronunciations of the word signorina (young woman). The term conflated all women’s interaction with African American and Allied soldiers with prostitution. Tombolo remains a symbol in the far-right imagination, with neo-fascist groups like Forza Nuova repurposing wartime propaganda against immigrants.

Post-war developments

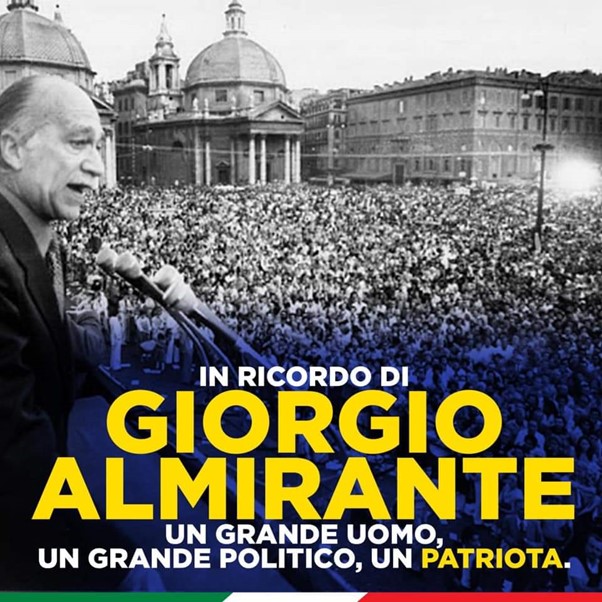

In present-day Italy, far-right and neo-fascist groups continue to mobilise familiar tropes. They have revived the anti-miscegenation ideology, but this time instead of focusing on American soldiers or colonial subjects, the ‘Others’ are immigrants and racialised minority groups. In Italy, far-right groups have embedded themselves in a political space that blurs the boundaries between the right wing and traditional fascism. It maintains an ambiguous stance towards the traditional movement, neither totally rejecting nor fully embracing it. Despite this ambiguous position, Fratelli d’Italia emerged as a successor to the Movimento Sociale Italiano (MSI) founded by Giorgio Almirante in 1946. Almirante had been a contributor and editorial assistant for the racist magazine La difesa della razza (The Defence of the Race). La difesa was not only antisemitic but also published many articles about racial mixing and Italy’s colonies. In a 1942 article, Almirante combined all of these racist elements in one place, arguing that Italian blood was what distinguished Italians from Jews and mixed-race people with African and Italian parentage. He argued that Italian racism should be based solely on ideas of blood, reducing the already-problematic area of biological racism to its most basic constitutive unit. In the same article, Almirante blames the fall of the Roman empire on Emperor Caracalla’s edict of 212 which proclaimed all free men citizens of Rome. Each year in April, activists gather to commemorate the killing of a member of MSI’s student wing Sergio Ramelli in 1975 with Fratelli d’Italia deputies often expressing support. This year, a crowd of 1500 neo-fascists took part in doing the Roman salute and over the years several Fratelli d’Italia deputies have tweeted supportive messages for these actions.

Giorgia Meloni’s tribute to Giorgio Almirante on Twitter posted 22 May 2020. Translation: In memory of Giorgio Almirante. A great man, a great politician, a patriot. Shared with the message: ‘Giorgio Almirante left us 32 years ago. Politician and Patriot of other times esteemed by friends and adversaries. Love for Italy, honesty, coherence and courage are values that he transmitted to the Italian Right and that we carry forward every day. A great man we will never forget.’ https://x.com/GiorgiaMeloni/status/1263764617999847424/photo/1/

In order to create a sense of historic continuity for the nation and its people a narrative was constructed to draw parallels between Mussolini’s rise to power through the March on Rome and Julius Caesar’s rise through a coup d’état, further emphasised by adopting Roman architectural styles and the Roman salute. These elements contributed to the notion that Fascism was a continuation of the past. But as well as looking to the past, the regime needed radical national projects to regenerate Italy to counter the notion that Italy was the ‘least of the great powers.’ However, in the present, in order to extend the genealogy of the party beyond being a product of Mussolinian fascism, Fratelli d’Italia have positioned themselves as the inheritors of the entirety of Italian history. Members of Fratelli d’Italia have appropriated historical figures such as Dante Alighieri and Giuseppe Mazzini. The culture minister Gennaro Sangiuliano claimed in January 2023 that Dante was the father of right-wing ideology which is similar to Mussolini’s attempt to demonstrate continuity between his regime and Ancient Rome.

Another continuity between Fratelli d’Italia, Almirante and fascism more broadly, comes in the form of current Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni’s rigid understanding of race as biological fact rather than as social construct. Last summer, Francesco Lollobrigida, Minister of Agriculture in Meloni’s government, denounced the ‘ethnic substitution’ of Italians by immigrants and urged Italians to have more children. Meloni defended him. Meloni’s position is that ‘races’ exist and are determined by physical difference and she contends that the left divides Italians by inserting groups that refuse to integrate. But not only has Meloni defended her minister, she has also made the same claim about ethnic substitution in the past, posting on her Facebook page in 2016 that Italy was seeing a dress rehearsal for ethnic substitution, pushing a version of the ‘Great Replacement’ conspiracy theory by claiming the majority of those migrating to Italy were African men. Meloni’s fear-mongering about an African threat is evident in her co-authorship of the book ”Mafia nigeriana. Origini, rituali, crimini” (Nigerian Mafia: Origins, Rituals, and Crimes) published in 2019. The book’s blurb claims that the rise of the Nigerian Mafia in Italy is ‘a phenomenon that is not only criminal in nature, but that […] has its roots in cannibalistic rituals and mixtures with Western sovereign mores.’

But these attacks on migrants extend beyond mere rhetoric. Public displays of violence and intimidation form part of the aesthetic of fascism, as Marinetti argued even before the advent of the fascist movement. The great innovation of fascism in the 1920s was the use of targeted violence to achieve their aims. As John Foot writes in Blood and Power (2022), ‘Cudgels, fire and castor oil’ were the methods used within the fascist cult of violence. CasaPound (named after American poet and fascist Ezra Pound) have not only protested any reform of Italian citizenship laws: they are also linked, alongside Forza Nuova, to attacks on migrants and wanton murders of African people.

Fascism remixed

A new genre has emerged in the murky online waters of the Italian far-right: Technoballila (Ballila being the name of the Italian equivalent of the Hitler Youth). It consists of techno remixes of fascist party anthems, Facetta Nera included. These videos attract young people nostalgic for a fascist past they never experienced, as the comment section on YouTube amply illustrates: ‘When Italy was a great and orderly country!’ ‘I wish I had lived during these glorious years’. The comments are also replete with people from other countries expressing their condolences for the fall of Mussolini highlighting the transnational appeal of the genre, while the videos often juxtapose footage from the 1920s and 1930s with the updated remixed songs. Naturally, these remixes represent more than just the modernisation of an older music genre. They create a stark example of the intersectional relationship between the classical and neo- iterations of fascist aesthetics designed to normalise the violent reality of the past. The repackaged versions of these songs are a microcosm of what the far right has done in terms of blurring the boundary between the classical and the new, and highlight the infiltration and parasitic integration of fascist symbolism and iconography within popular music. ‘Edgy’ humour and ‘just joking’-gestures about invading Ethiopia or marching on Rome are used to smuggle 1930s fascist propaganda into the 21st century. This ‘comic’ element of the new fascist aesthetic is perhaps what is most innovative about it. This online comic zone carves out a space for adherents to create a shared series of references and jokes that bind them together while also creating an outlet to air anxieties hidden behind humour.

This ‘comic’ element of the new fascist aesthetic is perhaps what is most innovative about it. This online comic zone carves out a space for adherents to create a shared series of references and jokes that bind them together while also creating an outlet to air anxieties hidden behind humour.

Technoballila is not unique as a form of music, nor is Italy as an example; in the 2010s, Fashwave emerged to co-opt 1980s synthesiser instrumental music with fascist symbolism, as happened to Swedish musician Robert Parker in 2016 (Reichsrock, White Power music, or the infiltration of the skinhead music scene in the UK in the 1980s are further examples of the process). As an instrumental genre, there are no lyrics in Fashwave music so the association between the genre and the ideology must be created by the category itself. Nancy S. Love argues in Trendy Fascism (2016) that the creation of new categories and sub-genres is a way to enjoy music that originated from Black American or Caribbean communities by erasing these origins, and to whiten the genre for proponents of neo-fascism. It represents the struggle to carve out a niche outside the mainstream without needing to completely reinvent the wheel artistically. Lazy revamps of pre-existing music seem a far cry from Marinetti’s call for a struggle for new art. It is effective nonetheless: Love claims that listening to neo-fascist music has acted as a means of recruitment or ‘conversion’ for many. Signs, symbols, music, and clothing can be transcoded and claimed by these movements.

Appeals to the youth, much as Mussolini and Marinetti made in their time, have driven recent far-right gains in European politics. Think of the chutzpah that is present in the footage of the youth wing of the Sweden Democrats after the EU elections, where the deputy David Lång was seen dancing and singing along to Gino d’Agostino’s L’Amour Toujours in the racist German contrafactum lyrics of the song. In a telling attempt at image-management, Lång’s leader, Linda Lindberg, sought to frame and excuse the ordeal as nothing but a drunken joke. Recently, Nigel Farage re-emerged as a popular figure in the UK on TikTok. As both a hardliner on immigration and a fun, regular guy you would have a pint with in the pub, he manages to appeal to several audiences with his varied personas. The often tongue-in-cheek adoration of Farage, his status as a walking meme and reality star, muddies the water about the harm he has caused in the UK. Despite being an elected member of Parliament, platformed regularly by mainstream media outlets as well as his inclusion on ITV’s I’m a Celebrity Get Me Out of Here last year, he is still construed as an outsider to an Establishment he pretends to be sticking two fingers up at. In the wake of the killing of three children in the town of Southport near Liverpool, Farage feigned ignorance, taking a ‘I’m just asking questions’ stance while deliberately spreading misinformation about the identity of the attacker. This strategic ambiguity and plausible deniability does the same kind of work as the ‘I was joking’ defence. Misinformation spread after these attacks lead directly to days of far-right riots driven by Islamophobia, racism, and anti-immigration ideologies. When the online spills out into the real world, the consequences are not so funny.